Westland Whirlwind

Westland Whirlwind

A twin-engine heavy fighter

The Westland Whirlwind was a British twin-engined heavy fighter developed by Westland Aircraft. A contemporary of the Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane, it was the first single-seat, twin-engined, cannon-armed fighter of the Royal Air Force and was the only Westland fighter to achieve operational status.

When it first flew in 1938, the Whirlwind was one of the fastest combat aircraft in the world, and with four Hispano-Suiza 404 auto-cannon in its nose, the most heavily armed. Protracted development problems with its Rolls-Royce Peregrine engines delayed the project and few Whirlwinds were built. During the Second World War, only three RAF squadrons were equipped with the Whirlwind but despite its success as a fighter and ground attack aircraft, it was withdrawn from service in 1943.

By the mid-1930s, aircraft designers around the world perceived that increased attack speeds were imposing shorter firing times on fighter pilots. This implied less ammunition hitting the target and ensuring destruction. Instead of two rifle-calibre machine guns, six or eight were required; studies had shown that eight machine guns could deliver 256 rounds per second. The eight machine guns installed in the Spitfire and the Hurricane fired rifle-calibre rounds, which did not deliver enough damage to quickly knock out an opponent. Cannon, such as the French 20 mm Hispano-Suiza HS.404, which could fire explosive ammunition, offered more firepower and attention turned to aircraft designs which could carry four cannon. While the most agile fighter aircraft were generally small and light, their limited fuel storage also limited their range and tended to restrict them to defensive and interception roles. The larger airframes and bigger fuel loads of twin-engined designs were therefore favoured for long-range, offensive roles.

The first British specification for a high-performance machine-gun monoplane was F.5/34 but the aircraft produced were overtaken by the development of the new Hawker and Supermarine fighters. The RAF Air Staff thought that an experimental aircraft armed with the 20 mm cannon was needed urgently and Air Ministry specification F.37/35 was issued in 1935. The specification called for a single-seat day and night fighter armed with four cannon. The top speed had to be at least 40 mph (64 km/h) greater than that of contemporary bombers – at least 330 mph (530 km/h) at 15,000 ft (4,600 m).

Eight aircraft designs from five companies were submitted in response to the specification. Boulton Paul offered the P.88A and P.88B (two related single engine designs), Bristol the single-engined Type 153 and the twin-engined Type 153A. Hawker offered a variant of the Hurricane, the Supermarine 312 was a variant of Spitfire and the Supermarine 313 a twin-engined design with four guns in the nose and potentially a further two firing through the propeller hubs, the Westland P.9 had two Rolls-Royce Kestrel K.26 engines and a twin tail.

When the designs were considered in May 1936, there was concern that two engines would be less maneuverable than a single-engined design and that uneven recoil from cannon set in the wings would give less accurate fire. The conference favoured two engines with the cannon set in the nose and recommended the Supermarine 313. Although Supermarine's efforts were favoured due to their success with fast aircraft and the promise of the Spitfire which was undergoing trials, neither they nor Hawker were in a position to deliver a modified version of their single-engined designs quickly enough. Westland, which had less work and was further advanced in their project, was chosen along with the P.88 and the Type 313 for construction. A contract for two P.9s was placed in February 1937 which were expected to be flying in mid-1938. The P.88s were ordered in December along with a Supermarine design to F37/35 but both were cancelled in January.

Westland's design team, under the new leadership of WEW 'Teddy' Petter (who later designed the English Electric Canberra, Lightning and Folland Gnat) designed an aircraft that employed state-of-the-art technology. The monocoque fuselage was tubular, with a T-tail at the end, although as originally conceived, the design featured a twin tail, which was discarded when large Fowler flaps were added that caused large areas of turbulence over the tail unit. The elevator was moved up out of the way of the disturbed airflow caused when the flaps were down. Handley Page slats were fitted to the outer wings and to the leading edge of the radiator openings; these were interconnected by duraluminium torque tubes. In June 1941, the slats were wired shut on the recommendation of the Chief Investigator of the Accident Investigation Branch, after two Whirlwinds crashed when the outer slats failed during hard manœuvering; tests by the A&AEE confirmed that the Whirlwind's take-off and landing was largely unaffected with the slats locked shut, while the flight characteristics improved under the conditions in which the slats normally deployed.

The engines were developments of the Rolls-Royce Kestrel K.26, later renamed Peregrine. The first prototype, L6844, used long exhaust ducts that were channelled through the wings and fuel tanks, exiting at the wing's trailing edge. This configuration was quickly changed to more conventional, external exhausts after Westland's Chief test pilot Harald Penrose nearly lost control when an exhaust duct broke and heat-fractured an aileron control rod. The engines were cooled by ducted radiators, which were set into the leading edges of the wing centre-sections to reduce drag. The airframe was built mainly of stressed-skin duraluminium, with the exception of the rear-fuselage, which used a magnesium alloy stressed skin. With the pilot sitting high under one of the world's first full bubble canopies and the low and forward location of the wing, all round visibility was good (except for directly over the nose). Four 20 mm cannon were mounted in the nose; the 600 lb/minute fire rate made it the most heavily armed fighter aircraft of its era. The clustering of the weapons also meant that there were no convergence problems as with wing-mounted guns. Hopes were so high for the design that it remained 'top secret' for much of its development, although it had already been mentioned in the French press.

L6844 first flew on 11 October 1938, construction having been delayed chiefly due to the new features and also because of the late delivery of the engines. L6844 was passed to RAE Farnborough at the end of the year, while further service trials were later carried out at Martlesham Heath. The Whirlwind exhibited excellent handling characteristics and proved to be very easy to fly at all speeds. The only exception was the inadequate directional control during take-off which necessitated an increased rudder area above the tailplane.

The Whirlwind was quite small, only slightly larger than the Hurricane but smaller in terms of frontal area. The landing gear was fully retractable and the entire aircraft was very 'clean' with few openings or protuberances. Radiators were in the leading edge on the inner wings rather than below the engines. This careful attention to streamlining and two 885 hp Peregrine engines powered it to over 360 mph (580 km/h), the same speed as the latest single-engine fighters. The aircraft had short range, under 300 mi (480 km) combat radius, which made it marginal as an escort. The first deliveries of Peregrine engines did not reach Westland until January 1940.

By late 1940, the Supermarine Spitfire was scheduled to mount 20 mm cannon so the 'cannon-armed' requirement was being met and by this time, the role of escort fighters was becoming less important as RAF Bomber Command turned to night flying. The main qualities the RAF were looking for in a twin-engine fighter were range and carrying capacity (to allow the large radar apparatus of the time to be carried), in which requirements the Bristol Beaufighter could perform just as well as or even better than the Whirlwind.

Production orders were contingent on the success of the test programme; delays caused by over 250 modifications to the two prototypes led to an initial production order for 200 aircraft being held up until January 1939, followed by a second order for a similar number, deliveries to fighter squadrons being scheduled to begin in September 1940. Earlier, due to the lower expected production at Westland, there had been suggestions that production should be by other firms and an early 1939 plan to build 600 of them at the Castle Bromwich factory was dropped in favour of Spitfire production.

Despite the Whirlwind's promise, production ended in January 1942, after the completion of just two prototypes and 112 production aircraft. Rolls-Royce needed to concentrate on the development and production of the Merlin, and the troubled Vulture, rather than the Peregrine. Westland was aware that its design – which had been built around the Peregrine – was incapable of using anything larger without an extensive redesign. After the cancellation of the Whirlwind, Petter campaigned for the development of a Whirlwind Mk II, which was to have been powered by an improved 1,010 hp Peregrine, with a better, higher-altitude supercharger, also using 100 octane fuel, with an increased boost rating. This proposal was aborted when Rolls-Royce cancelled work on the Peregrine. Building a Whirlwind consumed three times as much alloy as a Spitfire.

![]()

The various

Marks of

Whirlwind, all

produced at

Yeovil.

P.9 prototype - Single-seat twin-engine fighter aircraft prototype. Two built (L6844 and L6845), can be distinguished from later production samples by the mudguards above the wheels (although the first production sample (P-6966) had them as well), the exhaust system and the so-called 'acorn' on the joint between fin and rudder. L6844 had a distinctive downward kink to the front of its pitot tube, atop the tail not seen again in following models. L6844's colour was dark grey and not red, as is often stated. L6844 had opposite-rotation engines, L6845 had the same rotation engines as per production machines.

Whirlwind I - Single-seat twin-engine fighter aircraft, 400 ordered, 2 prototype & 114 production aircraft, total aircraft built 116.

Whirlwind II - Single-seat twin-engine fighter-bomber aircraft, fitted with under-wing bomb racks, were nicknamed 'Whirlibombers'. At least 67 conversions made from the original Mk I fighter.

Experimental variants - a Mk I Whirlwind was tested as a night fighter in 1940 with No 25 Squadron. The first prototype was armed with an experimental twelve 0.303" machine guns and another one 37 mm cannon.

Merlin variant - Westland proposed fitting Merlin engines in a letter to Air Marshal Sholto Douglas. The proposal was rejected but Westland used the design work already performed in developing the Welkin high-altitude fighter.

![]()

| General characteristics | |

| Crew: | One |

| Length: | 32 ft 3 in (9.83 m) |

| Wingspan: | 45 ft 0 in (13.72 m) |

| Height: | 11 ft 0 in (3.35 m) |

| Wing area: | 250 ft² (23.2 m²) |

| Empty weight: | 8,310 lb (3,777 kg) |

| Loaded weight: | 10,356 lb (4,707 kg) |

| Max takeoff weight | 11,445 lb (5,202 kg) |

| Powerplant: | 2 × Rolls-Royce Peregrine I liquid-cooled V12 engine, 885 hp (660 kW) at 10,000 ft (3,050 m) with 100 octane fuel each |

| Performance | |

| Maximum speed: | 360 mph (313 knots, 580 km/h) at 15,000 ft (4,570 m) |

| Stall speed: | 95 mph (83 knots, 153 km/h) (flaps down) |

| Range: | 800 mi (696 nmi, 1,288 km) |

| Combat radius: | 150 mi (130 nmi, 240 km) as low altitude fighter, with normal reserves |

| Service ceiling: | 30,300 ft (9,240 m) |

| Armament | |

| Guns: | 4 × Hispano 20 mm cannon with 60 rounds per gun |

| Bombs: | 2 × 250 lb (115 kg) or 1 x 500 lb (230 kg) bombs |

| Production | |

| Number built: | 116 |

| First flight: | 11 October 1938 |

All the above text based on / 'borrowed' from Wikipedia.

gallery

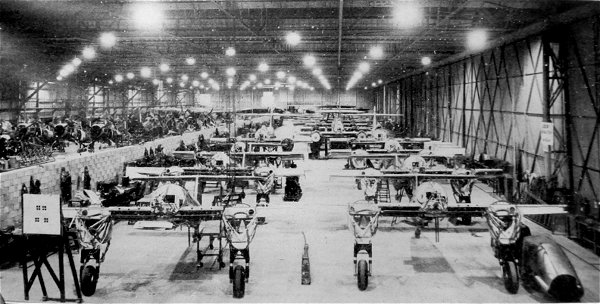

Westland Whirlwinds on the assembly line.

Westland Whirlwind second prototype, L6845, photographed at Martlesham Heath while being tested by the A&AEE, July 1939. Note the overall aluminium paint scheme, with polished spinners.

Whirlwind I undergoing fighter-bomber trials at the A&AEE. Note the under-wing bombs and the four cannon in the nose.

Westland Whirlwind in a rare Second World War colour photograph.

From July 1942 bomb racks were added to 67 Westland Whirlwind Mk I fighters converting them to Westland Whirlwind Mk II fighter / bombers.