Gloving in yeovil

The history of denner & vaughan

Glove Manufacturers of Reckleford

I am most

grateful to

Brian Vaughan

for permission

to reproduce the

following

history of the

Yeovil gloving

firm

Denner &

Vaughan, written

by

Arthur Denner

and his partner

John Vaughan

(Brian's

father)..

![]()

Courtesy of

Brian Vaughan

The brass plaque that was fixed to the Denner and Vaughan factory.

![]()

These notes have been completed jointly, started by Arthur Denner shortly before his death in 1989, and subsequently continued by his partner John, both from memory and the few remaining records.

DENNER & VAUGHAN

- Events

leading up

to the

formation of

the

business.

-

Formation of

the

partnership

and

overcoming

difficulties

of

commencing a

new business

in 1950.

-

Obtaining

premises,

equipment,

materials,

workers and

orders.

-

Expansion

problems,

leading to

the

establishment

of the Poole

factory.

-

Formation of

PG Company,

building of

new factory,

move of

Yeovil

factory to

Reckleford,

taking over

staff of

Thring and

Luffman.

- Decline

of fabric

glove sales,

changing to

leather

production

with

purchase of

Tavener

equipment

etc.

- The good

years with

Golden.

- The years of decline.

Phase One - The

Idea

In 1947 I left

the firm of

W

Tavener & Son,

Yeovil, where I

had been

employed as

'Sales Manager'

but in reality a

general dogs

body, and I

joined Seager

Bros Ltd of

Sherborne as

Factory Manager.

John Vaughan had

at this time

just been

de-mobbed from

the RAF and

reinstated in

his old job as

Manager of

Seager Bros'

factory at Bower

Hinton, Martock.

War-time controls of materials, new premises and equipment, and indeed everything needed by manufacturers to get production of peace-time goods going, were still in force. In the clothing trade, there was the 'utility' mark which governed the specification and price of all garments, and the greater percentage of sales had to conform to these specifications. All garments could only be supplied against clothing coupons, and manufacturers could only obtain permits for materials as a proportion of their pre-war purchases. Thus, some found it more profitable to sell their quotas of material than to make them up.

Seager Bros was owned by a London wholesale firm, Cocksedge & Kither, who I soon discovered were not interested in making gloves, but only in making money. The manufacturing side had been run down during the war, equipment and machines 'lost' or neglected, and male cutters had to be reinstated with no leather for them to cut, and not enough female machinists to sew what the did cut. John and I worked out plans to reorganise the business on a long term basis but met with a lot of underground opposition from some of the staff, and a total lack of interest from the management. Altogether a classic case of what is now called 'middle management frustration'.

We eventually came to the conclusion that even with conditions as they were in 1950, we would be better off both in spirit and in pocket if we could start a business of our own. John could get the necessary permit as he was officially war disabled - the great difficulty was getting finance at reasonable terms.

In the spring of 1950, to events happened which made up our minds. A 'mole' managed to persuade Norman Kither that a manager at Martock was a needless expense and he was given notice. An aunt died and, under the terms of my grandfather's will, I was left a small sum of money - not a lot but enough to start us off in business and pay off the mortgage on my house. As I was confident the 'mole' would soon be operating against me, I promptly gave in my notice and left the firm in July 1950.

Phase Two - Getting Started

The chief

stumbling blocks

to commencing a

business such as

ours in 1950

could be

summarised as -

A.

Obtaining

finance to cover

initial expenses

and

non-productive

period.

Our initial

capital amounted

to £2,150, of

which I

contributed

£1,500 and John

£650. A

partnership

agreement was

drawn up by

Donald Burgess

of Poole &

Company,

Solicitors,

South Petherton,

and a

partnership bank

account was

opened at the

South Petherton

branch of the

Westminster

Bank. The

manager, Mr

Green, who knew

John personally,

was most helpful

and agreed to

allow us an

overdraft

secured against

the deeds of my

house when we

got into

production.

B.

Obtaining

necessary permit

to enable a new

business to be

started, and

premises in

which to

operate.

At this time it

was necessary to

obtain a permit

before a new

manufacturing

business could

be launched.

Permission was

usually given to

war-disabled

people and, as

John was in

receipt of war

disablement

pension, we

journeyed to

London to state

our case to the

appropriate

Board of Trade

department. We

found the office

we needed in

Horseferry Road

and, after

filling in forms

and being

interviewed by a

rather junior

clerk, we were

given the

necessary

permit. We were

pleasantly

surprised by the

ease with which

we obtained the

permit, and set

about trying to

find premises.

This was not

easy, as we

needed something

scheduled for

industrial use

and which could

be rented at a

figure we could

afford.

After several false starts we heard that a Mr Newbery, who owned a small garage at Preston on the outskirts of Yeovil, might be able to help us. We found that he was the owner of a block of derelict farm buildings lying between Preston Road and Westbourne Grove, most of which had been converted into lock-up garages. A brick built cowstall had been converted into a workshop and was being used by GA Merritt to make photographic enlargers. Some buildings were used by a family called Cannon, trading as Welldoone Fencing Company who made cast concrete fencing posts. A stone built stables, carriage house and hayloft had been recently vacated by a part-time car repairer, and these premises were offered to us at a rental of £5 9s 0d per week. Electricity was laid on, and there was use of ladies and gents toilets in the adjoining squash courts which had been made from the old barn. We therefore clinched the deal and took possession in September of 1950.

We now had an address and it was possible to get our own letterheads printed and apply for a telephone to be installed. Clothing coupons had recently been abolished but a regulation requiring a proportion od manufacture to conform to a 'tax free' Utility Schedule was still in force. Any goods sold which did not conform to this schedule had to bear Purchase Tax, and invoices had to bear the supplier's PT registered number. Firms who had registered PT numbers could buy and sell among themselves without paying or charging tax. It was thus necessary to approach the local Customs & Excise Officer in order to get the necessary registration. At that time the Customs & Excise Office was in Church Street, overlooking the churchyard (on the second floor of what had been the living quarters of Somerville's grocery shop).

The Chief Officer, Mr Gibson, one of the old school of Civil Servants, was most helpful once he had made sure we were likely to have the resources and knowledge to set up a permanent business. He suggested, however, that we should appoint an accountant to advise us on Income Tax, whose figures would be accepted by Inland Revenue and Customs & Excise, and would start us off with a proper book-keeping system. He suggested a man who had recently opened an office in Yeovil, Reg Pearce, and as John remembered him from school days, and he would be unlikely to have business connections with any of our competitors, we went to see him. We explained our aims to him and he agreed to act on our behalf. He set up a simple book-keeping system and gave us many useful hints. He continued to act for us until his early death, when his junior partner, Brian Collins, carried on in his stead.

C. Getting necessary plant, equipment and materials, ie leather, cotton cloth, sewing threads, etc.

From the start we had decided that it would be best to concentrate on the manufacture of cotton fabric gloves rather than leather. Leather was very difficult to obtain, as the sources of supply of raw skins had been disrupted, the cost was so high we would have been unable to finance a viable output, and it was most difficult to train workers in this material. The Martock factory of Seager Bros had specialised in fabric glove manufacture, so John had some good contacts among the suppliers of the material and among women who made up gloves in their own homes. At that time, many of these outworkers owned their own specialised sewing machines, so they were not tied to any particular manufacturer.

Before any gloves could be made up, they had to be cut out. To do this we needed a press and a set of webs (knives). It was essential that these should be made to dimensions which would produce a glove of the shape and fit acceptable to trade buyers. It seemed to be agreed in the trade that fabric gloves produced by a well known manufacturer were the best, so we bought several pairs and pulled them to pieces! The best firm in the trade for making up glove knives was WH Hallett, then in Sherborne Road, so we consulted him on the matter. By chance he had a set of knives to almost the exact dimensions we needed, made for a customer who had then cancelled them, so he offered them to us on long term credit. We also bought a guillotine knife and he loaned us an old hand lever press. Jack Eason, from Sherborne, built up a cutting bench round the knife. John made up some partitions from 2" x 2" and hardboard, and did the work with whitewash. A small boarded off room which had been the harness room became our office, furnished with a filing cabinet, some chairs and a table. For heating we used a number of oil stoves.

D.

Engaging a

nucleus of

skilled workers.

John, with his

knowledge of

cutting both

leather and

fabric, would be

able to commence

the process of

initial

production.

At about this

time we had

another stroke

of luck, as on

our doorstep

appeared a Mr

and Mrs Jones

who had heard we

wanted workers.

He was a fabric

glove cutter who

had not gone

back to his old

firm when

de-mobbed, but

had gone to work

in the stores at

war-time Lufton

Camp. As it was

rumoured this

would soon

close, he wished

to get back to

his old trade,

at first on a

part-time basis.

His wife, who

had also worked

for a local

factory on

fabric gloves,

wished to go out

to work. George

Jones proved to

be a steady but

reliable worker

and his wife a

very adaptable

machinist who

was quite

willing to have

a go at any

progress work,

as well as glove

making for which

she had her own

machine.

Although they

lived at

Stoke-sub-Hamdon,

they were quite

willing to make

the daily

journey by bus

as we were on

the direct bus

route, Stoke -

Yeovil. Other

small

manufacturers

helped us out

with specialised

sewing for which

we did not have

the necessary

machinists and,

by the end of

October, a small

quantity of

finished goods

were being

produced.

Advertisements placed in the Western Gazette during December 1950. (A brosser was a modified whipstitch).

We then set about creating a sales organisation. W Tavener & Son employed agents selling on commission to the retail trade and as our fabric gloves would not compete with the leather gloves sold by them, I approached several of them offering the agency for our gloves. The London agent, Fred Doe, was most enthusiastic and was most useful to us as he had a good connection with export buying houses as well as the large retail stores, that being before 'group buying' became the usual practice. Harold Thomas, the Northern Counties agent, also agreed to carry our goods which, however, he appeared to view with some suspicion. It soon became clear that we could sell far more than we could make, especially when our products went into the stores, when it was seen by buyers and sales staff they were well made and well finished. Most were in the 'utility' price range, but we never made the mistake of undercutting our competitors, selling at a little below the maximum controlled price. Thus, when all overheads might increase due to expansion, we would still have a profit margin without increasing prices. Our sales for October 1950 were £43, November £137, December £317, January 1951 £370, February £638 and March £598.

While this was encouraging, we felt disappointed with our low output. This was primarily due to the shortage of female workers who were either already skilled machinists or who would be willing to learn. This shortage was general throughout the glove manufacturing industry in the Yeovil area, and was due to the number of more lucrative and less tedious jobs now available to women in the district. We therefore looked around the area within a radius of 40 miles to find a place with a surplus of juvenile female labour which could be trained to our requirements. Poole seemed to be such a place, and the Juvenile Employment Officer was very interested and helpful. Once again we began a search for small premises at a rent we could afford, but they were all either too large, in the wrong locality, too expensive, or all three. Eventually an estate agent persuaded us to buy a site on a new industrial estate being developed in Lea Road off Sterte Avenue, so that we could put up a small building on the site. This site cost us £211 4s 6d including legal fees and the architect's fees, regarding the planning permission which was granted on 20 April 1951, cost us a further £21.

In the duplicate of the planning application, it was interesting to note that while details are given of the foundations, drains and toilets, no mention is made of the size of the proposed building, but the estimated cost is given as £3,800. As our total capital was only £2,150, and that by now was fully committed in plant and goods in work, the fact that we could even think of building even a small factory shows how confident we were in our own future. Although we now had a site and had planning permission for a building to be erected, we now had to get Board of Trade permission to spend money on the building materials necessary. The regional office dealing with this was in Reading, so we drove there in John's old Ford 10, taking with us original Export Orders we had received hoping to impress the officials of the BoT. The treatment we received soured our relationship with Government departments for evermore. Our case did not even get a fair hearing and when we pointed out that our ability to earn foreign currency, we were told that although we had the orders, we would never get the necessary materials as there was a war in in Korea! The fact that the raw material for our cloth came from Egypt carried no weight! We retired, bitter but unbowed, to think again. Gradually we picked up a few more workers and output improved. The frustrating thing was that we knew the market for our goods was there, we were confident that our suppliers would back us - the only thing holding us back was shortage of female labour.

At this juncture Arthur was taken ill and was never able to complete his narrative. Sadly he died in 1989 so the following history has been gathered together by his partner, John.

By sheer determination and a degree of bloody-mindedness we gradually gathered together a nucleus of indoor staff but we needed more space. A loft over our ground floor was in use as a store by Mr Newbery and we were able to persuade him to rent it out to us. We set about turning it into a sewing machine section, together with a finishing and inspection department, also office space, so leaving the ground floor for a cutting room and packing facilities. We salvaged a set of stairs from somewhere, bought army surplus tables, chairs, shelving, etc. from around the auction sales. Timber for partitioning was still a scarce commodity but our old friend Jack Eason - being as much a rebel as we, following our treatment form the BoT bureaucrats - came to the rescue by using supplies left over from the very generous 'quotas' meted out to the farming fraternity. The improved facilities helped us enormously for a while but we still had Poole in mind and were quite determined to establish ourselves there.

1952 / 53

Having established our reputation for reliable merchandise, we again investigated the Poole area and this time were fortunate in finding suitable premises - a large single storey, one room building with the advantage of being quite near the site we had purchased and retained in 1950. So far, so good - our next hurdle was a suitable teaching machinist capable of both training and controlling teenage labour and who would also be prepared to go to Poole. Things were falling into place and as, by this period, controls were off building materials, we enlisted the skills of Jack Eason and his staff to equip the premises to our specialised requirements.

Pre-war glove making machines were in a pretty poor shape by this time so we embarked on purchasing new machinery from the Singer Sewing Machine Company; we interviewed, with the help of the local Juvenile Employment Office, girls who were shortly leaving school. We selected twelve and, by January 1953, we were embarked on an exercise designed to test our instinct to the full. With Arthur initiating and supervising sales, together with office and administration and John covering all aspects of manufacturing, we were busy. Initially, John journeyed to Poole twice weekly, the staff there responded magnificently and from the first twelve girls, there was but one failure, so, by Easter of 1953, we were ready for a further intake of girls for training.

We were still operating as Denner & Vaughan at this time but our production expansion through Poole led us to consider widening our sales outlets. Denner & Vaughan could only supply the retail and export outlets; the wholesale houses were closed to anyone supplying the shops direct. The answer was to create a separate company to tackle the wholesalers and, in May 1954, the Poole Glove Company Ltd was set up as a solely owned subsidiary of Denner & Vaughan with its separate identity and administration. A London agent with wholesale contacts was appointed, also for Birmingham, Manchester and Glasgow, and business began to flow, thus creating the cash flow we always considered so essential in a trade largely restricted to Autumn deliveries, necessitating stock piling over six to eight months of the year.

We always held the view that the age old custom of using the outworker or home worker system was both unsatisfactory and certainly not economic; reliance could never be placed on such an arrangement that gave no guarantee of production continuity. Our success in the Poole factory proved our point beyond all doubt as, within six months of commencement with all raw labour, we had a production capacity from inside the factory greater than anything we had achieved in Yeovil over 2 to 3 years using outworkers.

From the outset of establishing our own business we were prepared to take as little by way of salaries as possible and use what profit we may produce to plough into the business and so increase the working capital. We had assistance from the bank from time to time - always it drove a hard bargain and we were thus wary of using the facility too often.

Speed of production from the intake of raw materials to the finished glove, strict attention to quality, customer requirements and delivery dates, were the only way to establish customer / supplier relationships, leading to a satisfactory cash flow situation. This we achieved with the setting up of the Poole factory. The speed of production increased dramatically from 8 / 10 weeks using the outworker system to 3 / 4 weeks with an all indoor staff. Even this was improved upon with larger orders coming through from the wholesale section who favoured a much smaller range styles giving larger quantities of each. The retailers preferred a spread of orders over a whole range of styles, making difficulties for production planning. So in 1955 it wa agreed that John would move to Poole to supervise the whole project and also enable him to train staff in the cutting process, as by now Yeovil could not supply sufficient cut gloves to keep the two factories running. The Yeovil based factory was attracting useful export contracts from Australia and New Zealand, also the larger retail companies.

All this led to another goal - that of building our own factory on the land at Sterte Avenue we had acquired in 1950. We required a purpose built brick building capable of providing space for upwards of forty sewing machinists plus ancillary staff, and necessities to run a complete indoor production. It was built by direct labour using local self-employed tradesmen and the whole operation was directed and supervised by a building contractor friend of John's - Bill Bond, who travelled down from Kent at weekends. It was commenced in March 1956 and occupied in December of the same years at a net cost of £4,000.

In 1957 we were fortunate enough to attract the attention of Marks & Spencer who were seeking supplies of fabric gloves and, following negotiations, a pilot order was produced to their satisfaction and so ensued a very happy relationship. Half the Poole production was taken up over fifty weeks of the year, the styles were simple and in only four shades, thus making long production runs possible and improving productivity to such an extent that the period of time from cutting of cloth to the boxed gloves was down to two weeks. Together with other supporting orders, we had several years of consolidation and, in 1960, the Yeovil unit moved from Preston to leasehold premises available in the town centre. We were also able to acquire more staff from a recently closed factory unit and so, after ten years of careful and solid endeavours, the Partners had reason to feel satisfied with their progress.

Courtesy of

Brian Vaughan

Denner and Vaughan staff pose outside the company's works on the first floor of the Nautilus Works, Reckleford, in 1964.

However, nothing as they say is forever and, in the early 1960s there were ominous signs that the fabric glove industry was about to face problems of severe competition from the Far Eastern countries such as Hong Kong, Taiwan and the Philippines - this added to the fact that gloves as a necessary part of a lady's attire were being written out of fashion by the magazines. The foreign competition was very fierce indeed. Trade delegations to the Board of Trade were met with the amazing statement that "The Textile Industry of this country is quite expendable" - the actual words of the moguls who reminded us that we must give support to the Third World countries who were dependent on textile manufacture to aid their stricken economies. Bulk orders began to decline and Marks & Spencer also showed signs of pulling out of the Fabric Gloves section to move over to either vinyl or lower grade leathers. Staff at Poole began to decline as we were unable to recruit new trainees; we were also losing trained staff to a local electronics factory requiring nimble fingered operators and offering very high rates of pay to get them - way out of our reach in the face of severe price competition.

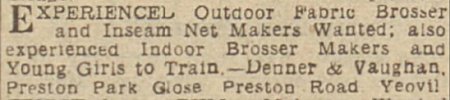

Courtesy of

Brian Vaughan

Denner and Vaughan gloves in 1964. At left fashion gloves (don't you wish they'd make a fashion come-back?) and at right what was described as "Denner and Vaughan's new feminine washable driving glove with a maximum-grip leather and nylon palm and crimp nylon "waffle" knit back. Colours are black and fashion shades."

So for a couple of years life was rather difficult, but the glove trade had a history of ups and downs as we both knew from our experience. We tried a variety of ways to increase sales; we put on a full-time salaried traveller to organise a sales programme - he proved a very expensive disaster, but the fact had to be faced that the fabric glove trade was being decimated by imports from abroad and beyond recall.

We turned our attention to the possibilities of breaking into the leather trade by initially buying ready-made gloves and filtering them into our sales organisation, but not very successfully. We knew that a great deal of work was required to establish a viable set up. We even embarked on the idea of turning to leather clothing at Poole but quickly decided it was not for us.

How things turn on unexpected events - for two years the going was tough but, in the Autumn of 1964, Arthur received a telephone call from his old boss, Ernie Tavener - a Yeovil leather glove manufacturer of some years standing - to say that he wished to retire and would Arthur like to look at the possibilities of taking the manufacturing unit including equipment, customers and whatever staff could be accommodated. Such an opportunity could not be refused and there was no hesitation by either Arthur or John that this was to be seized on immediately. Satisfactory arrangements were agreed with Mr Tavener, our Yeovil premises were adapted to take on six glove cutters, sewing machinists and other ancillary staff. Contacts were made with the Tavener customers, most of whom were prepared to support us provided we maintained their required quality standards.

Leather glove production demanded greater capital outlay and the production costs of one pair of leather gloves were infinitely greater than that of twelve pairs of fabric. The Poole factory was becoming very run down so the decision was taken to close and sell the building to provide an immediate injection of capital to get the venture under way, which was accomplished by the spring of 1965. John returned to Yeovil to oversee the new leather production and what was left of the fabric trade. Further injections of cash were made by guarantees by Arthur, and when John disposed of his house in Poole.

Among the customers acquired was an American businessman, Mr A Golden, who was anxious to obtain a regular supply of gloves for the golf scene. The potential was tremendous given that the Americans were fanatical when it came to the game of golf. Specifications and quality were all important in that the glove had to fit the hand like a second skin and be made from the finest leathers available. Both men's and women's gloves were required - and for the most part, for the left hand only - some right hand would be required to meet the needs of left handed players, to to four styles only but in a whole range of colours. We met in London, we struck an immediate rapport, styles were agreed and a planned delivery schedule worked out all in the matter of a week. The deal consisted of a regular two week delivery by air, the quantity to grow as fast as the production expanded which meant that, with continuity of supply, a steady cash flow would be forthcoming and provide the necessary anchor to enable us to clothe the home trade fashion glove customers whose orders were always fragmented over many styles, and their delivery concentrated into a two month period in both Autumn and Spring, thus tying up capital over long periods of stockpiling.

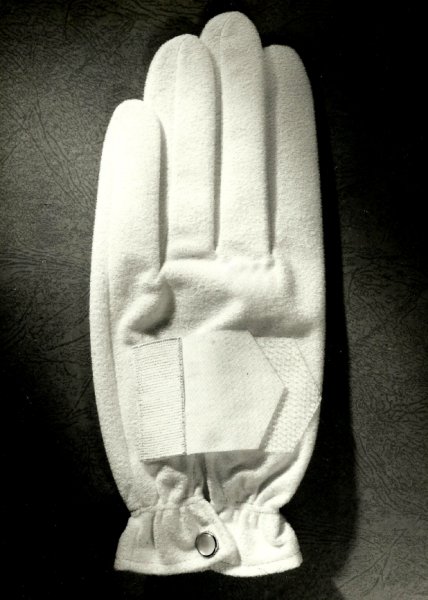

Courtesy of

Brian Vaughan

A Denner & Vaughan golf wet weather glove.

The excellent relations we developed with America led to visits there by both partners together and separately over the ensuing years, a period which we looked back on as our 'Golden Years'. Leather production, not being as easy as fabric, meant that reluctantly we were forced to return to the out or home worker system and, in the light of our Poole experience, we were not too happy about it. However, using Poole as an example, we set about organising the work force to lessen the production time from leather to box. The benefit of the golf glove lay in the fact that the orders were big, styles small and so, as with Marks & Spencer production, long runs were possible. So once the gloves were cut - all by hand - the indoor sewing staff were harnessed to mostly preparation work to supply a steady flow to be available for the outworkers. Gradually production increased and a fairly reliable flow from them increased enough to allow us to keep our American client reasonably content, albeit always wanting more.

A lack of demand for fashion gloves on the fabric side led us into sports demand in the field of gloves for football goalkeepers. This kept the work force together and added to the ever needed cash flow.

1973 - 76

All aspects of

the clothing

industry

revolved around

changing

fashions and the

glove trade was

certainly no

exception, and

was something

which every

manufacturer

needed to accept

and deal with.

The build up of

competition from

abroad and lack

of appreciation

by Government

departments of

the need to so

arrange trade

treaties to

avoid wholesale

slaughter of

home based

industries spelt

death to the

textile section.

Clothing and

gloves of all

kinds poured

into the country

from the

so-called

developing

countries, the

irony being that

they were

supported with

interest free

loans of finance

from this

country.

Protests were

useless and it

was obvious that

within a short

time the

industry would,

after two to

three hundred

years in the

area and other

areas in the

country, go out

of existence.

By dint of

our American

trade we hung

on, the home

business became

less and less

and then a

problem arose in

the knowledge

that the lease

of our premises

in Reckleford,

Yeovil, would

not be renewed,

and we were left

with only a year

to stay - so the

question arose

"should we close

or move if

suitable

premises could

be found?"

Arthur was

desirous of

taking

retirement but

was reluctant to

do so in all the

circumstances.

In the event,

however,

premises were

found, the move

was made and

Arthur was able

to take a well

earned

retirement in

the Autumn of

1974.

The golf trade

continued,

together with

the remnants of

both leather

fashion and

fabric sporting

gloves, but with

the Korean

manufacturers

making serious

inroads into the

American golf

glove market,

the signs of

demise were

becoming

serious. John

made his last

journey to the

USA to study the

precise

situation but it

was obvious that

the Korean

prices on offer

were way out of

reach - to

attempt to do so

would be

suicide.

With Arthur having retired and John coming up to 65 years, the decision was taken to go the way of most businesses in the area and bring the business to a close. There were no buyers to be found interested in declining glove factories and so sadly staff were gradually made redundant and the business, after a happy partnership period over some 26 years, came to an end. From the start and all the way, it was a challenge, a gamble, a risk, fun and, above all, successful. The mutual trust of each other was all embracing and I, John, could not have had a better partner and friend.

Throughout the firm's existence, both partners took considerable interest in the welfare of the industry through the local Association of Glove manufacturers, the National Association of Glove Manufacturers and the Glove Guild of Great Britain. These were bodies set up to deal with all aspects of the trade, involving the Wages Council, training boards and government departments. Arthur became involved locally serving as Chairman and President and was instrumental in setting up a machinist training school in Yeovil, to which all local manufacturers contributed financially and by sending in trainees.

John became involved in the National Association of Glove Manufacturers, first as a committee member, later as Chairman of the Fabric Section, and became President for the year 1969 -70. He also served on the government sponsored Clothing and Allied Textile Training Board which became a bureaucratic nightmare, became bogged down and was eventually abolished.

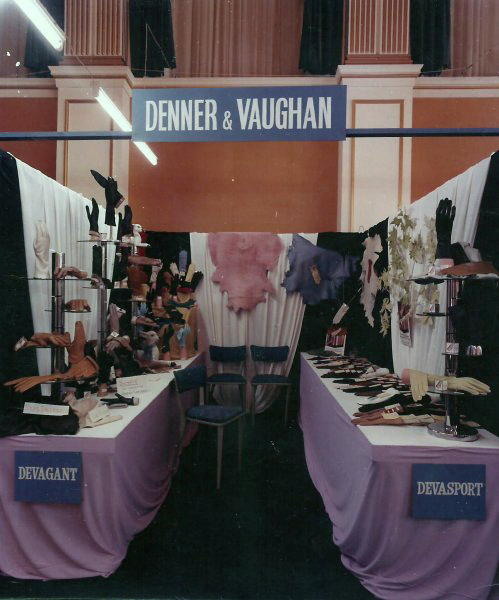

Courtesy of

Brian Vaughan

The Denner & Vaughan exhibition stand at the 1965 British Glove Fair.

Through the

Glove Guild,

trade fairs were

organised yearly

and held at

Brighton and

London, in which

the firm

participated by

taking

exhibition

facilities, and

in 1973 and

1974, against

all comers won

the trophy given

by the

Worshipful

Company of

Glovers for

export

achievement.

The good, the

bad and the

indifferent

years were

overall happy

ones and it is

sad to think

that a once

thriving

industry that

gave employment

to so many

people over

several hundreds

of years, has

disappeared into

oblivion - but

that, as they

say, is life.

Courtesy of

Brian Vaughan

Staff of Denner and Vaughan celebrate winning the Export Challenge Cup, donated by the Worshipful Company of Glovers of London to the British glove manufacturer with the best export performance for 1972/73. The cup was presented at the British Glove Fair in February 1974. Holding the cup are John Vaughan (left) and Arthur Denner (right).