Yeovil Political Union

Yeovil Political Union

Formed in the wake of the 1831 Reform Riot in the town

Less than two weeks after the Yeovil Reform Riot of 21-22 October 1831, the Bristol Mercury, edition of 1 November 1831, expressed the general feeling across the country during this period as follows: "When a spirit of combination appears among the Higher Orders, to withhold from the People their rights, it is deemed, even by the most prudent, proper to meet this spirit by a similar combination on the part of the People; and if the result should be a conflict, where will the Anti-reform Spiritual and Temporal Lords be, in a month? On the army they can place no confidence, for that is at the King's disposal; besides, from the admixture of the soldiery with the people, the former are become, three parts out of four, reformers; and would hardly obey their officers, were they called on the fight for the boroughmongers. On the Yeomanry they know they cannot rely; for besides that the 'Unions' could annihilate them in a week, the bulk of the yeomanry would not draw a sword in their favour. Their only resource is their tenantry; and to them their conduct has been such, (we instance the Duke of Newcastle, and Lords Salisbury, Stamford, Warwick, etc) that they could not, for very shame, ask them to act in the field in their favour. They have, therefore, nothing to place in contact with Political Unions of the People; and if the latter in the event do, as they no doubt will, beard them in their halls - thwart them in their magisterial capacities - interpose between them and their game-law victims - make known their every act of domestic and public tyranny - in fine, if they make their country seats too hot for them - who but themselves will they have to blame for the whole? Had it not been for the oppression of the Aristocracy - an oppression they will not even now quietly relinquish, - the people would never have thought of Political Unions. They have, however, been in a manner driven into them; and the Bishops and other Anti-reformers must take the consequences."

![]()

During the late 1820s there was ever-increasing discontent among the working-class population across the county and demands for social, economic and political reform were being put down by reactionary governments and especially, and perhaps unsurprisingly, a hostile House of Lords. This was chiefly due to the electoral system which was corrupt and unrepresentative. At this time Members of Parliament tended to be from Britain's richest families and represented towns and boroughs where they had major control. In 1830 most of the British population was still excluded from voting, so they had no influence over the law-making process that affected their lives and consequently the poor had to endure low pay combined with harsh working conditions. Voting took place publicly so coercion became rife and, of course, the working-class people often worked for and/or lived in property owned by their MP.

In 1825 William Huskisson, President of the Board of Trade, removed all restrictions on imported gloves and exposed Yeovil glove manufacturers to unlimited competition from France. Since glove making employed something like 80% of Yeovilians, a widespread depression hit the town. To quote Hayward "The distress was real enough: outdoor relief [i.e. benefit without entering the workhouse] in the parish rose to over £600 in 1825-6 and to £1,000 in 1831-2; the Mendicity Society reported in 1832 that 1,027 persons applied for relief, of whom 927 were helped (there were 149 imposters and two were prosecuted!): Outdoor relief was given to 170 persons, mainly glove workers, in 1833." The resulting depression underlies the political unrest demonstrated by the 1831 riots and, perhaps, the activity of a nascent radical Yeovil Political Union. This combination of political and economic factors would stimulate and encourage popular collective action in Yeovil.

Hetherington’s Poor Man's Guardian was mainly read outside of London, and its weekly reports on the proceedings of the meetings of the National Union of the Working Classes in London was likely the source of the various Political Unions.

The Yeovil

Political Union,

probably formed on the

model of the

Birmingham

radical

organisation,

was officially formed in

early November

1831 in the wake

of the recent

Yeovil Reform

Riot of 21

to 22 October

1831. Although political

unrest had, in

fact, been

brewing in the

town for several

weeks

beforehand.

The Yeovil

Political Union,

probably formed on the

model of the

Birmingham

radical

organisation,

was officially formed in

early November

1831 in the wake

of the recent

Yeovil Reform

Riot of 21

to 22 October

1831. Although political

unrest had, in

fact, been

brewing in the

town for several

weeks

beforehand.

The emblem of the Yeovil Political Union was the ancient Roman 'fasces', a bundle of rods bound up with an axe in the middle. This had been a symbol of authority in the Roman Republic.

The Yeovil Political Union aimed, through the distribution of leaflets and holding meetings, to create an informed public opinion in order to bring pressure on the government for a programme of reform.

The 15 November 1831 edition of the Bristol Mercury reported the following - "Political Unions have been formed at Chard and Yeovil, the objects of which are to obtain, by every just and legal means, such a Reform in the Commons House of Parliament as may ensure a real and effectual Representation of the lower and middle classes of the people in that House; to promote peace, union, and concord among all classes of his Majesty's subjects; and to guide and direct the public mind into uniform, peaceful, and legitimate operations."

At its inaugural meeting, the chairman contended that the Union was created "not for the spirit of the Constitution, but to put down anarchy and confusion, in whatever form it may appear... We are ready, like every other good and loyal subject, to place ourselves under the command of the civil authorities, should the riotous scenes that have lately convulsed the town and neighbourhood happen again."

The Yeovil Political Union sent a number of petitions to parliament, held meetings and rallies and expressed their aims in the press (notably the Poor Man's Guardian and True Sun).

Postscript

By the middle of the 1830s, the Yeovil Political Union had tended to fade into the background, being slowly superseded by the Chartist movement that existed from 1838 until 1857. This was the first mass movement driven by the working classes. It grew following the failure of the 1832 Reform Act to extend the vote beyond those owning property.

In 1838 a People's Charter was drawn up for the London Working Men's Association. The Charter had six demands:

- All men

to have the

vote

(universal

manhood

suffrage)

- Voting

should take

place by

secret

ballot

-

Parliamentary

elections

every year,

not once

every five

years

-

Constituencies

should be of

equal size

- Members

of

Parliament

should be

paid

- The property qualification for becoming a Member of Parliament should be abolished

In June 1839,

the Chartists'

petition was

presented to the

House of Commons

with over 1.25

million

signatures. It

was rejected by

Parliament. This

provoked unrest

which was

swiftly crushed

by the

authorities. A

second petition

was presented in

May 1842, signed

by over three

million people

but again it was

rejected and

further unrest

and arrests

followed. In

April 1848 a

third and final

petition was

presented which

was also

rejected.

Despite the

Chartist

leaders'

attempts to keep

the movement

alive, within a

few years it was

no longer a

driving force

for reform.

However, the Chartists' legacy remained and by the 1850s Members of Parliament accepted that further reform was inevitable. Further Reform Acts were passed in 1867 and 1884. By 1918, five of the Chartists' six demands had been achieved - only the stipulation that parliamentary elections be held every year was unfulfilled.

gallery

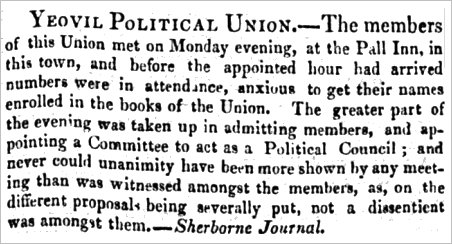

A report from the Sherborne Journal, reproduced in the 11 November 1831 edition of the Sun (London) and repeated in its edition of 14 November.

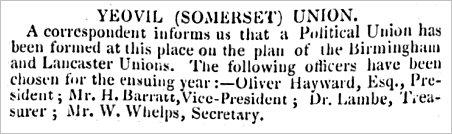

Also from the 11 November 1831 edition of the Sun (London).

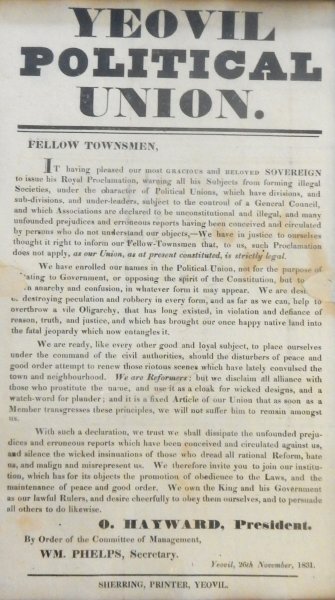

Courtesy of South Somerset Heritage Collection

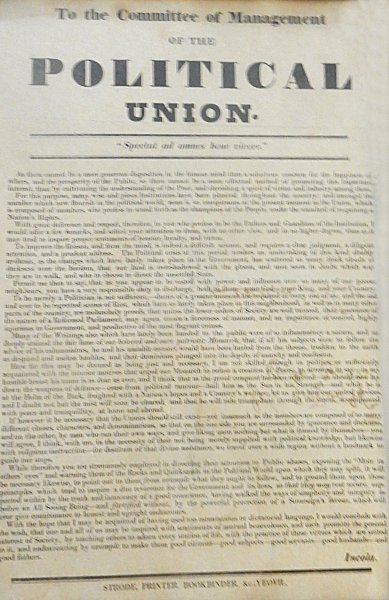

This handbill, dated 26 November 1831 (just under a month after the Yeovil Reform Riot) and issued by the Yeovil Political Union is worth retelling legibly, as follows -

YEOVIL

|

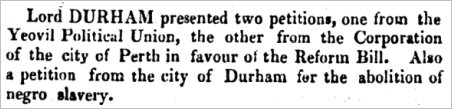

A snippet from the 9 May 1832 edition of the Sun (London). At this stage, petitions and meetings were the only options for action open to the Yeovil Political Union in order to bring pressure on the government for a programme of reform.

&nb

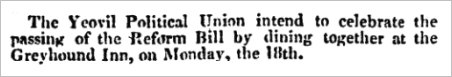

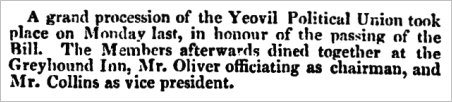

Reported in the 18 June 1832 edition of the Salisbury & Winchester Journal, there's nothing like having a celebratory dinner. This was to be held in the first incarnation of the Greyhound Inn in South Street, not today's building (currently 'The Keep').

Courtesy of South Somerset Heritage Collection

A handbill published by 'Incola' (Latin for resident) and printed by Sherring of Yeovil, that had commended the Committee of the Political Union to a "more responsible direction of its members" in the light of the actions taken during the October 1831 Yeovil Reform Riot.

Courtesy of South Somerset Heritage Collection

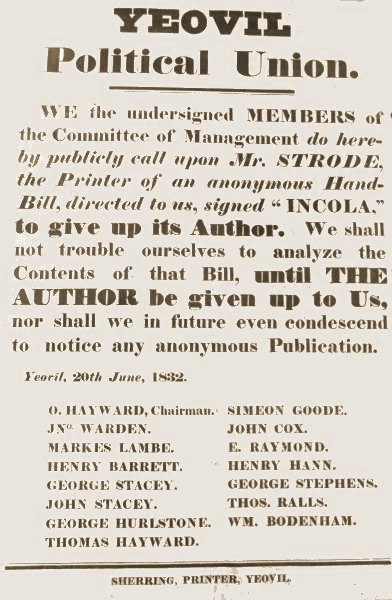

A handbill dated 20 June 1832 and signed by the committee of the Yeovil Political Union in response to the handbill published by 'Incola' (above).

The

Chairman of the

Yeovil Political

Union was

Oliver Hayward

(1788-1837) of

Yeovil.

The

Chairman of the

Yeovil Political

Union was

Oliver Hayward

(1788-1837) of

Yeovil.

Included among the committee were glove manufacturer and later Mayor of Yeovil Edward Raymond (photographed at the left), surgeon Markes Lambe, who lived at (today's) 1 & 3 Princes Street, George Stephens of Clarence Place, bacon and cheese dealer William Bodenham of Silver Street, butcher George Hurlstone of Middle Street, Sheriff's Officer John Cox of Hendford, Thomas Hayward, a man of independent means, and glover Simeon Goode - both living in South Street.

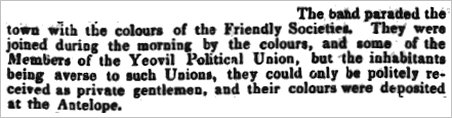

The Yeovil Political Union were clearly not welcome everywhere. This report is from the 21 June 1832 edition of the Dorset County Chronicle describing celebrations and a parade in Sherborne.

As reported in the 25 June 1832 edition of the Salisbury & Winchester Journal, the Yeovil Political Union had more support in Yeovil.

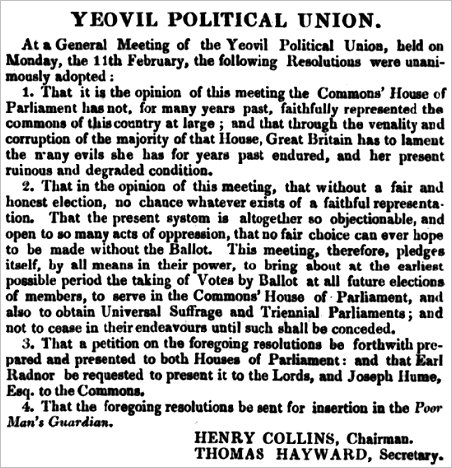

A report on a General Meeting of 11 February 1833 from the 2 March 1833 edition of the Poor Man's Guardian. The new Chairman of the Yeovil Political Union was glove manufacturer Henry Collins the Younger of Court Ash House.

Another week, another meeting, another petition - reported in the 9 March 1833 edition of the Poor Man's Guardian.

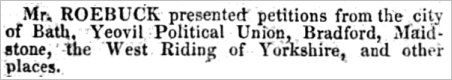

... and, as reported in the True Sun on 11 March 1833, the petition was duly delivered.

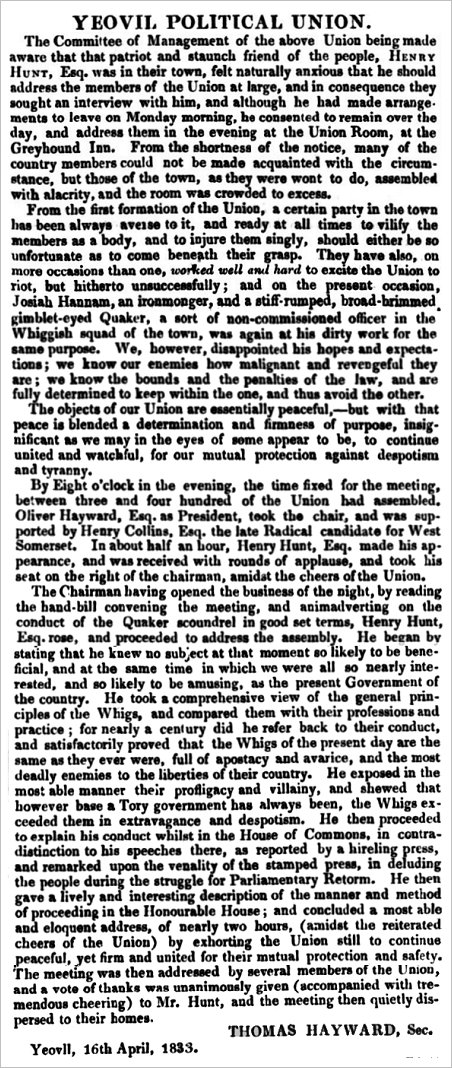

From this report from the 27 April 1833 edition of the Poor Man's Guardian, it becomes clear that the arch-enemy of the Yeovil Political Union was the "... stiff-rumped, broad-brimmed, gimblet-eyed Quaker" Josiah Hannam, ironmonger of the Borough.

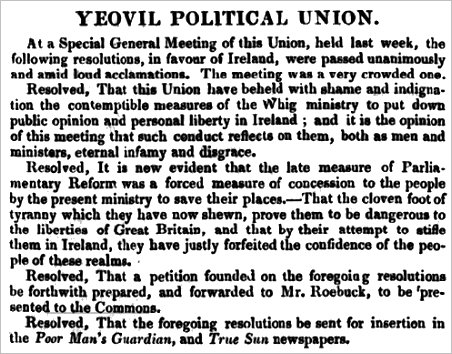

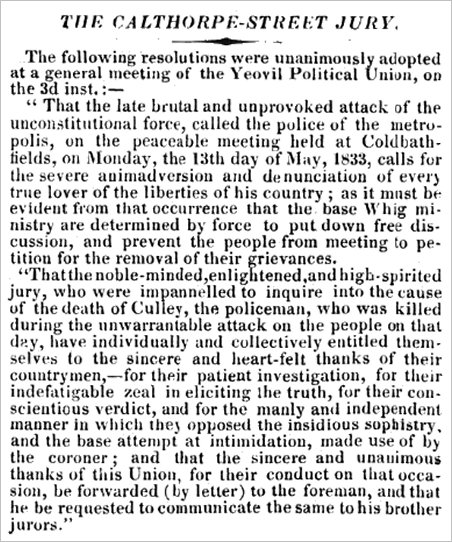

This report, from the 10 June 1833 edition of True Sun, shows the language and style of rhetoric emanating from the Yeovil Political Union on a regular basis.

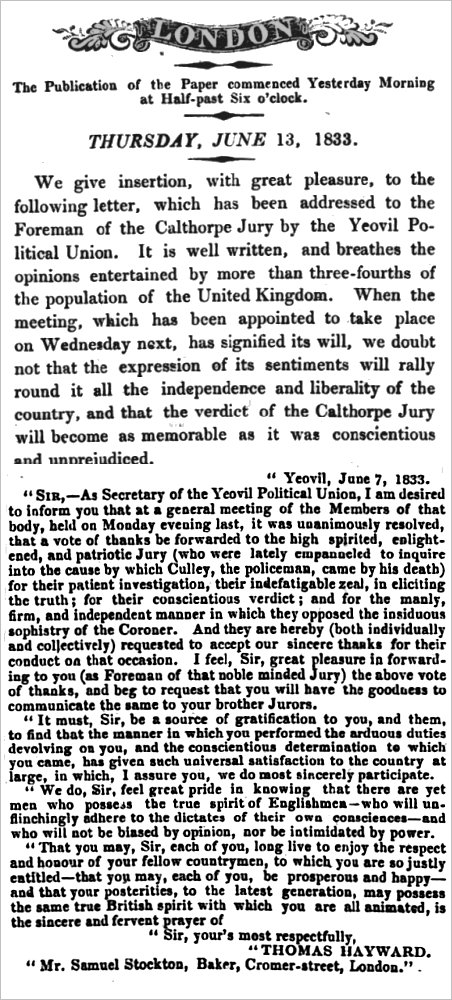

That the Yeovil Political Union was reaching an ever-widening audience, this interesting letter was published in the 13 June 1833 edition of the Morning Advertiser.

A further example of the Yeovil Political Union's rhetoric is encapsulated in this report from the 22 June 1833 edition of the Poor Man's Guardian.

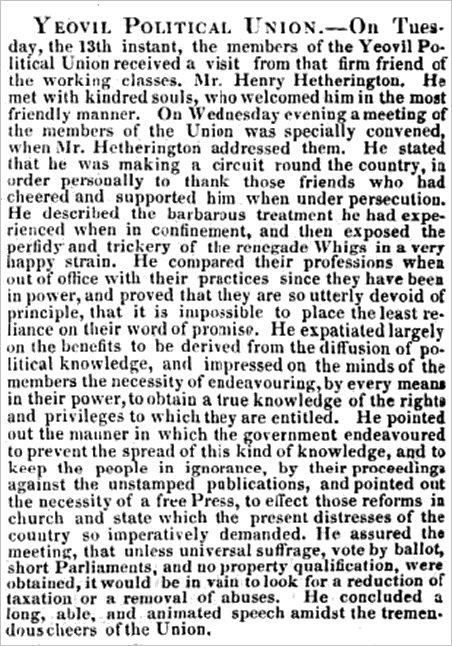

A report, from the 22 August 1833 edition of True Sun, from the visit and address given by Henry Hatherington to members of the Yeovil Political Union.

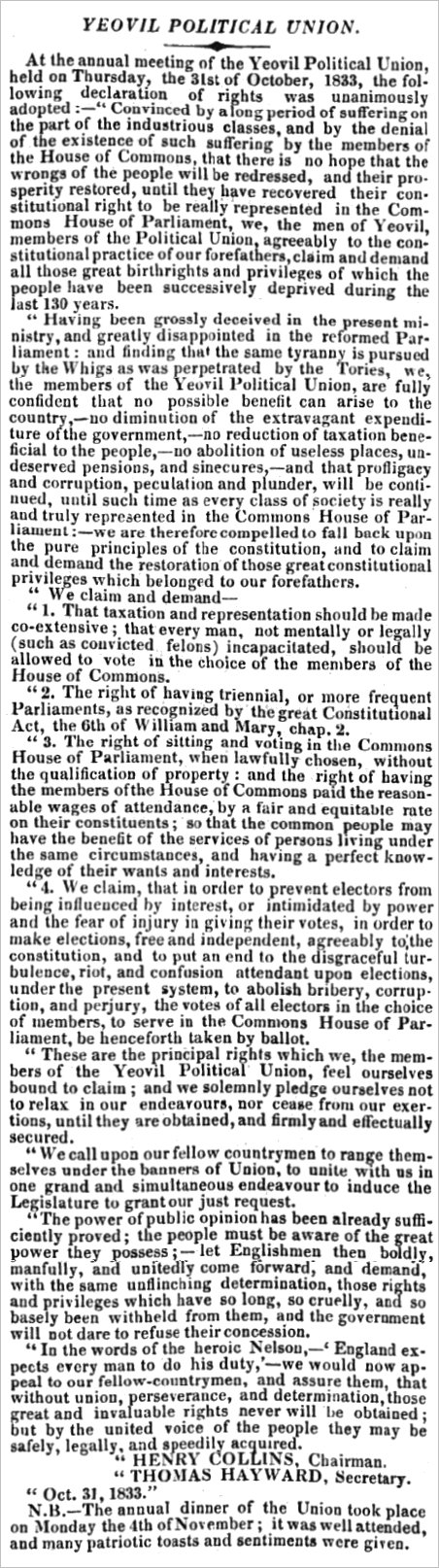

A lengthy report from the 12 November 1833 edition of True Sun concerning the Annual Meeting of the Yeovil Political Union, listing its grievances and demands of Parliament.

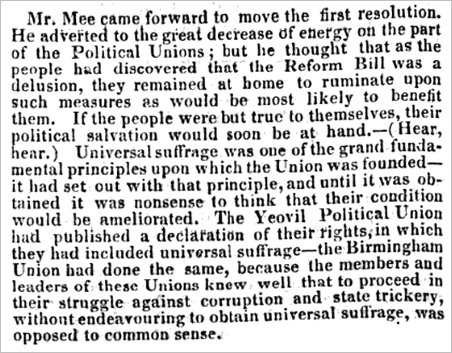

Part of a report on a London meeting of Political Unions in the 19 November 1833 edition of True Sun in which it becomes apparent that the Yeovil Political Union was something of a leading light having published a declaration of rights.

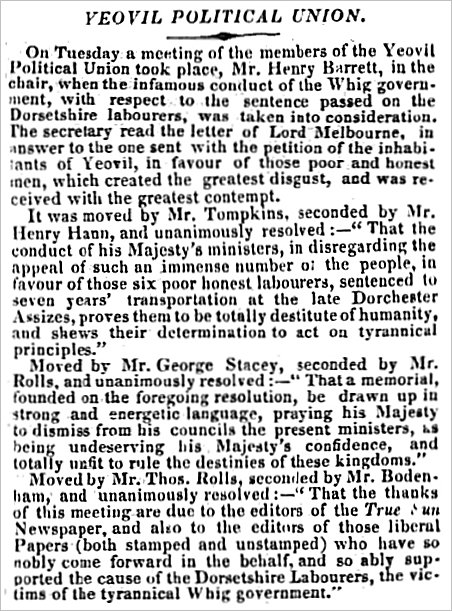

This report, from the 26 April 1834 edition of True Sun, shows the support that the Yeovil Political Union offered to "six poor honest labourers" we know today as the Tolpuddle Martyrs.