education in yeovil

yeovil high school for girls

Founded in 1891

Henry Cobb, in his early life known as Harry, was born in the spring of 1833 at Copford, Essex. In the 1851 census Harry was still living at home, aged 17 and working as a printer's apprentice. In the spring of 1860 Henry married Anna Coates at Woodbridge, Suffolk and in the 1861 census Henry and Anna were living in Ipswich, Suffolk, where Henry described his occupation as editor & publisher. By 1881 Henry Cobb had moved his family yet again, this time to Yeovil. The 1881 census listed him as a 'Bookseller & Printer, employing 1 assistant, 1 man & 6 lads' and was living above his bookshop at 79 Hendford, on the corner of Porter's Lane and next door to Stuckey's Bank. It was Henry Cobb's bookshop that was to be later the gentleman's outfitting department of Lindsay Denner's store.

It was in 1891 that Henry Cobb, together with Colonel Marsh and others, founded the Yeovil High School for Girls, colloquially known as Yeovil High School, and his daughter Fanny became its first headmistress initially with just a dozen pupils. She was assisted by a Second Mistress, Miss Mothersole, and her father Henry acted as School Secretary.

A company was formed called the Yeovil Girls' Public Day School Co Ltd. The school grew rapidly and plans were made to build a new school in a new development which was to become The Park. In 1896 the new school building opened and an advertisement was placed in Whitby's Yeovil Almanack Advertiser of 1896 which stated that "New and spacious School buildings, with the latest improvements in ventilation and sanitary arrangements, have been erected in The Park."

In 1905 the governors of the school made an offer to the county education committee to provide instruction for pupil teachers. At the same time the governors attempted to convert the school into a public trust, thereby making it eligible for grants. The following year of the county council arranged to send to the Pupil Teacher Centre at the Yeovil Girls' High School "those girl pupil teachers who are at present attending the Sherborne Centre, and also any girl pupil teacher who may hereafter be appointed to schools in the Yeovil Union District and in Crewkerne, Hinton St George, Merriott or Misterton, subject to satisfactory terms being raised regarding the fees." The annual fee per pupil teacher was fixed at six guineas.

It was at this time that the school was formally recognised as a secondary school and a Board of Governors was appointed. There were to be 10 governors, of which at least three were to be women and there were also to be three co-optative governors of which at least one was to be a woman. The first co-optative governors included its founder Henry Cobb, solicitor William Marsh, William Alfred Hunt dental surgeon and at this time mayor of Yeovil, John Vincent JP, John Luffman gentleman and architect Joseph Nicholson Johnson.

The annual tuition fee was set at 12 guineas (about £1,300 at today's value) with borders paying an additional £40 (about £4,100 at today's value) per annum. An extension was completed in 1908 at a cost of about £900 which provided "An excellent chemical and physical laboratory and a good cooking room". At this time there were 57 pupils, three pupil teachers and one student teacher.

In 1912 a special sub-committee of the County Council's Education Committee reported "the Clerk to the Governors is Mr H Cobb, the father of the Headmistress. He is, himself, a Governor, but receives an honorary of £10 per annum (about £960 at today's value) for his services, a payment which should not be made to a Governor without the sanction of the Board of Education. We are strongly of the opinion that, in the interests of the school, Mister Cobb, who has reached a somewhat advanced age, should be relieved of the duties of clerk and be succeeded by someone who is not a Governor."

In 1920 negotiations were held to hand the school over to the care of the County Council and at the same time a site was sought on which to build a new school. However because of financial difficulties the proposed do school would not be built for at least 10 years.

Harper noted "For a year or two leading up to her retirement in 1924, Miss Cobb seems to have conducted a running battle with the Education Committee regarding her retirement. The Committee informed the Governors that Miss Cobb had passed the age limit had requested that they (the Governors) inform Miss Cobb that the Committee could not consent to her retaining the post after 31 December 1923 and to invite her to tender her resignation to take effect from that date. However, it was July 1924 before Miss Cobb finally retired after being headmistress of the Yeovil High School for Girls for 33 years. At the same time that Fanny Cobb retired, so did her sister Amy who had taught needlework at the school and was also the housekeeper and her sister Emma who was head of the Preparatory School and also taught music part-time.

One effect of the school being taken over by the County Council was the fact that the preparatory class would have to be discontinued - officially. However, unofficially, Miss Cobb was planning to continue this class in her home, and, in 1923, she was doing just that with the blessing of the county. The Yeovil Preparatory School then came into being, and Miss Cobb ran this 'successful experiment in co-education' as the Western Gazette called it, until 1936 when she finally relinquished control."

Following the retirement of Fanny Cobb, the new headmistress was Miss MM Bone who introduced more modern ideas into the school in both the curriculum and its organisation. Nevertheless the cramped conditions of the school buildings became a growing problem during the 1920s and 1930s meaning that many Yeovil girls had to go without a secondary school education or had to journey to neighbouring towns. Even the Guide Hut in Everton Road was bought into service for the junior form. It wasn't until 1946 that Park Lodge was acquired and adapted as an annex to the High School, although conditions were inadequate by today's standards with a lack of equipment and poor heating. Having said that, some parts of the main building were still lit by gas and electricity was not installed until 1948.

Following the education act 1944 the schools status changed in 1945 when fees were abolished and it became a fully maintained state school, admitting all pupils on the results of the common entrance examination that was held throughout the county. At this time the school had 252 pupils.

|

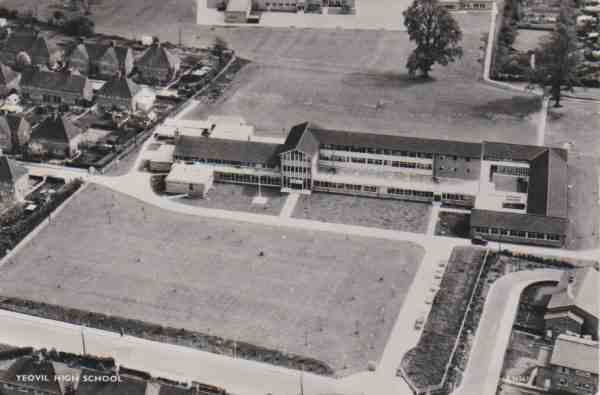

Teacher's dream comes true Three hundred girls move on Monday into a school that Yeovil has been waiting 30 years for. It is the three-storied ultra-modern Yeovil Girls High School at Stiby Road. Costing £108,000, it ranks as Somerset's most up-to-date school, and is the first grammar school to be built in the county for over 20 years. The school, which commands a sweeping review of Yeovil from its lofty site, was started exactly two years ago. It can justifiably be described as a teacher's dream, and is grandiose compared with the school's old premises at the park. The classrooms are spacious and airy, and have been tastefully decorated in pastel shades. There will be ample room for the 306 pupils, who must be thankful that the days of dark, over-crowded rooms are over. Everywhere in the building one is struck by the airiness of the rooms, in most of which there are only two solid walls - the other two are of glass. In fact, Mr Schillabeer (head of the Yeovil building firm to whom the contract was given) says over 10,000 square feet of glass have been used. In the assembly hall and library, special acoustic, sound-absorbing ceilings have been provided. Every possible facility has been installed - rooms for needlework and arts and crafts, pottery bay, library containing three or four thousand books, promenades, spacious cloakrooms, showers, changing blocks, and playing fields and tennis courts. Yes, the girls of Yeovil High School will find themselves in very different surroundings next term. But, as the French say, the more things change, the more they remain the same. The setting may change, but the policy and traditions will not. The 17 mistresses will still maintain discipline by firmness only: there are no severe or set punishments. Unchanged also will be the yellow and white uniform of the school, and the Pegasus badge, bearing the words Palma non sine pulvere - the palm of victory is not one without the dust of battle - a maxim that has long been borne out in the school's long struggle for new premises. Western Gazette, 10 April 1959 |

Nevertheless, despite having a new school that number of pupils had increased and by 1962 there were 360. Once again the resultant cramped accommodation led to a cry for extra classrooms and these were eventually erected by 1965. By 1971 the number of pupils had increased to 447 many of whom were accommodated within an ever-growing collection of temporary huts.

In 1974 the school changed from being a girls' grammar school to a mixed comprehensive school, thus ending its 83 year history. The original school buildings in The Park are at present (2013) being converted to offices, Park Lodge is now sheltered housing for the elderly and the Stiby Road school is now Westfield Pre School.

|

Yeovilians

remember... "I was still at YHS in 1959 when the school moved from 45 The Park and Park Lodge to Stiby Road. I can well remember the smell of the varnish on the new floors and the "plastery" smell of the new building. I must confess that I didn't like it very much - I liked the quirkiness of the old buildings and at the rather characterless Stiby Road there was a rule that if you had a class on anything other than the ground floor you had to go up a staircase on one side of the building and could only go down again by continuing up to the very top floor and taking another staircase which was right over on the other side - no going back again, or descending from the floor you were on if not the top one - I'm sure that kept us fit! Because of the new floors we were supposed to wear Clarks' "Everywhen" shoes only, but they were not only "fogey" but were expensive and not everyone's parents were willing or able to pay out the money for a new pair of shoes when a pupil owned a perfectly good pair that weren't yet worn out! The new school had something which we hadn't had in the previous buildings - showers! However, these showers didn't have nice cubicles, but just heavy green canvas curtains between them which some of the girls found it amusing to pull back. I, for one, hated this, having had an upbringing of total modesty! The Stiby Road premises must have saved us an awful lot of time between classes as everything we needed was on site. Previously we had had to walk (in a neat crocodile and in a "one way" system, as shown in one of your photographs) from 45 The Park to Park Lodge (not very far, but it still took time) and back again, since the Science Block was in the garden of Park Lodge and certain classes were taught in specific rooms. For instance, the Domestic Science room (complete with both gas and electric stoves and a Rayburn so that we could learn all types of cooking), the well equipped gym (which doubled as an assembly hall) and some other form rooms were in 45 The Park. The Art Room was situated in what used to be the attic of Park Lodge, with sky-lights which were very suitable for the kind of work we did there. Another time-consumer was the fact that we had no dining room and those who partook of school dinners which were compulsory if you didn't go home (you had to produce a doctor's certificate to say you were on a special diet if you wanted to bring sandwiches!) had to walk, again in crocodile, from the assembly point in front of Park Lodge, to the Centenary Hall in Clarence Street, near Brutton's Brewery. School uniform was very strict although, by the time I started at the school in 1954 the velour hats had been phased out and we had berets, with the Pegasus school badge on the front and a button on the top. We had navy blazers or gabardine raincoats, navy pinafore dresses (much nicer than the gym-slips of former years) or navy skirts and white blouses. Our ties were navy with gold and silver stripes and, as I think you already know, the blazer badge was Pegasus the winged horse with "Palma Non Sine Pulvere" underneath - "No Palms Without Dust", or "don't expect to get anything without working for it"! It was possible to earn a "Deportment Badge" for conducting oneself in an erect manner (I slouched around, so never got one) and the First and Second Eleven hockey teams wore white or yellow sashes (I didn't have one of those either, being rubbish at games). We young girls used to try to get away with some sort of individuality - ankle socks pulled up too far, berets with badges turned down so that they didn't show, skirts longer than the regulation length (obviously this was in the days before mini-skirts raised the opposite problem for the staff). We didn't get away with much as I think the staff were aware of the fact that, on the way to the Centenary Hall we had to walk past the rather "posh" fee-paying Park School where the uniform was rather more spectacular and, to our minds, desirable: long bottle green capes and quartered berets with different coloured tassels for each of the school's "houses" - I remember the tassels being pale blue, mauve and yellow, and I think the prefects' were white. Eating sweets (or anything else) when outside in school uniform was strictly forbidden and we were expected to look immaculate at all times. There was no punishment, as such, but the mere threat of a visit to Miss Jackson, the Headmistress, was enough to keep us toeing the line. Once at the Centenary Rooms (down a rather horrid alleyway and up a dark and dismal staircase), we were seated on forms at long tables for about eight girls, a mixture from each year, with a sixth former in charge. The staff sat at a table to one side of the hall, with Miss Drury the school's Second Mistress, as head. There was a rumour that Miss Drury couldn't eat anything red or pink because she was a Quaker! We girls were really silly! Our school dinners were brought in big metal containers from some way away - I think it may even have been as far as Taunton! Monitors from each table queued up in a side room and were served the food, each carrying two or three plates back to the rest of the girls at their table. We also had water in a jug and multi-coloured plastic beakers and used to contrive to make an awful mess with it. Some of the school dinners were rather odd - I can remember having beetroot with orange segments and mashed potato on occasions! There was always a dessert and a groan used to go up when we found it was tapioca or sago - the ubiquitous "frog spawn" of everyone's schooldays! I remember we used to have competitions when seated at tables out of sight of the staff table - "frog spawn" fired from a dessert spoon at the dado (the Centenary Rooms were decorated in cream paint and brown varnish and were far from clean), where it stuck and then trickled down behind the piano! The winner was the one whose projectile stuck longest before sliding down and we used to inspect from time to time to see how the debris was faring before being cleaned up! As I said, the Centenary Rooms were not terribly clean, with dusty bare wooden floors and beams high above us. Now and again we used to see a girl go up to the staff table, holding out her plate (rather like Oliver Twist, but not asking for more) to ask if she could have another dinner as something nasty - dust or cobwebs - had descended from the beams onto her plate! It was all good fun! Unlike many other schools, there was no playground, as such, at 45 The Park and Park Lodge. Instead, breaks were spent in the garden of Park Lodge where there was a sort of concrete "island" where the younger girls could skip and play hopscotch whilst the older girls used to stroll around the gardens, or sit in huddles and gossip (mainly about boys and clothes, as I remember!). The modern Science Block took up quite a large portion of the gardens and consisted of two classrooms, cloakrooms and a laboratory where Biology was taught. In my time the Physics and Chemistry lab was in the 45 The Park building, although I think the Park Lodge lab may have been used for Phys and Chem as well. The garden consisted mainly of lawns and pathways with some very nice shrubs and ornamental trees. Unusually, there was a Ginkgo tree and a lovely feature of the garden was the Weeping Ash, just outside the Sixth Form Common Room. This tree was fenced off early in the year by the gardener/caretaker, Mr Hurt, and his assistant, his son-in-law, Mr Austin, so that the thousands of crocuses which were planted underneath many, many years before, could grow. I always remember the yellow ones coming out first, followed by the mauve and white ones later. As the Ash tree was, of course, deciduous the crocuses were very much on show. Once they had died down, the ropes were taken away and we were able to hide under the tree which by then had leaves on it, and which provided a beautiful "tent". There were also bee hives in a separate part of the garden which was not open to the girls taking their break - you normally only went in if you were a member of the Beekeeping Club, run by Miss Greaves, the Art Mistress. Extraction day was great fun as we set out, veiled, hatted and gloved, with smokers to make the bees drowsy while we stole their honeycombs. The combs were then taken over to the Domestic Science room in 45 The Park where we cut the "lids" off the cells, put the honeycombs into an extracting machine (a sort of hand-cranked centrifuge, rather like a spin-dryer) where they were spun so that the honey was ejected from the cells. We then turned on the tap at the bottom of the extractor and poured the honey into jars. A little "perk" of this process was that (unknown to Miss Greaves), we used to chew bits of the beeswax we'd cut off the tops of the cells because there was a certain amount of honey left on them, and then threw the chewed wax down behind the Rayburn! I wonder if it's still there? Incidentally, my mother was a housemaid at Park Lodge as a young girl when it was a private dwellinghouse, before it was taken over by the school. She therefore knew of various "secrets" of the house - for instance, a cupboard with a false back that led into another cupboard in the adjoining classroom (these had formerly been bedrooms, so why there was a "secret" door in the cupboard is a matter for conjecture!). My knowledge of that led to some quite funny adventures. When we were messing about one day four of us hid in the cupboard in our form room and the English mistress (Mrs Phillips, an Irishwoman) came into the classroom, probably realised that something was going on and stood leaning against the cupboard door so that we couldn't get out. We then panicked a bit, found the catch and opened the "secret" door in the back of the cupboard (this was a bit like "The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe"!) but instead of Narnia we found ourselves in the cupboard in the next classroom. Not knowing what else to do, we burst out suddenly in the middle of the Maths lesson that was going on in the adjoining room, tipping over a desk and nearly giving Miss Wills (the Maths mistress) and the rest of her class heart attacks! Thereafter the four of us had to stand on the landing between lessons until the teachers arrived, lest we should do something else as awful!"

|

gallery

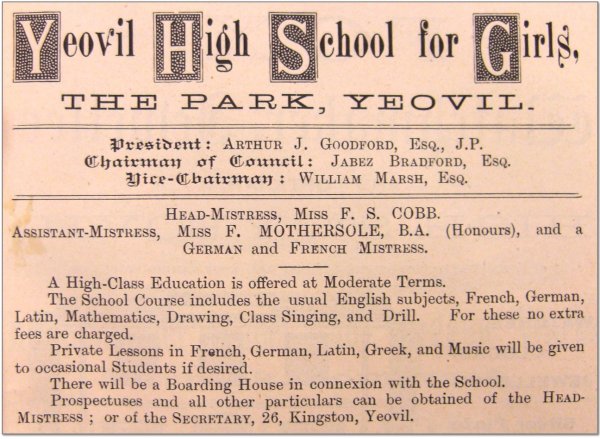

Advertisement for the Yeovil High School for Girls in the 1892 edition of Whitby's Yeovil Almanack Advertiser.

This photograph

features in my

book 'Yeovil

From Old

Photographs'

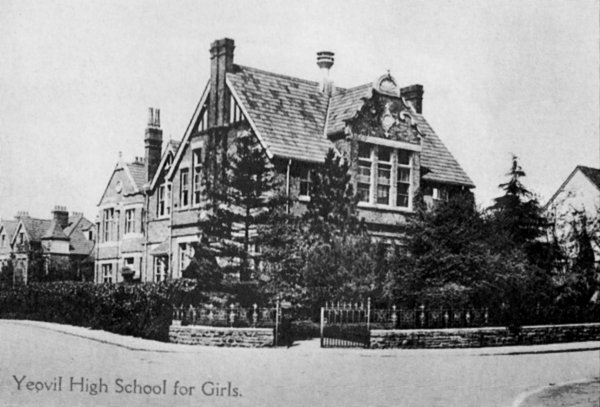

An early postcard of the new, purpose-built Yeovil High School for Girls, probably dating to just after its opening in 1906. It is now called Park House.

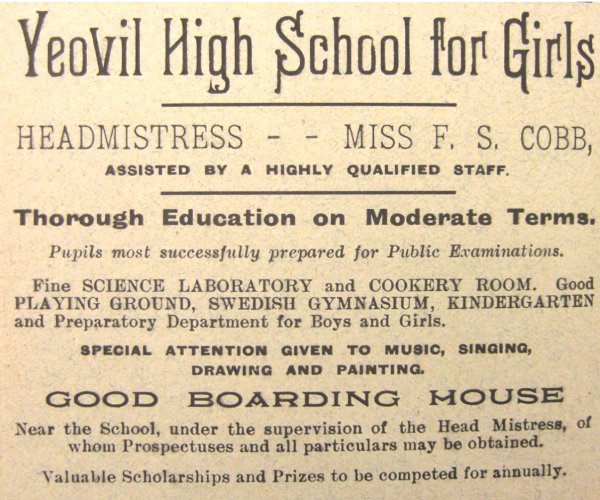

Advertisement for the Yeovil High School for Girls in the 1916 edition of Whitby's Yeovil Almanack Advertiser.

A photograph of 45 The Park, probably taken during the early 1950s.

The Park Lodge annex, again probably photographed in the early 1950s.

|

Yeovilians

remember... .... and thanks to Patricia Ann Smith for these reminiscences "Oh - gosh! How that brings back memories! The 'modern' building on the left was the Science Block and was the form room for my form in about 1959 - just before the school transferred to the new building in Stiby Road. There was a ginkgo tree in the Park Lodge garden, plus a weeping ash with crocuses underneath and we kept bees there as well (under the guidance of Miss Greaves, the Art Mistress)." |

The new school buildings at the Stiby Road site, opened in 1959 with the official opening in October 1960.

From my

collection

... and the school buildings seen from the other direction.

Courtesy of Bill and Audrey Robertson

The old school building in the Park, photographed in the 1990s when it was used as the art department of Yeovil College. Notice in the foreground, sitting in the flowerbed, is the old font from Christ Church.

![]()

The following is

a series of

photographs

published in the

July - September

1954 issue of

the Somerset

Countryman.

From my

collection

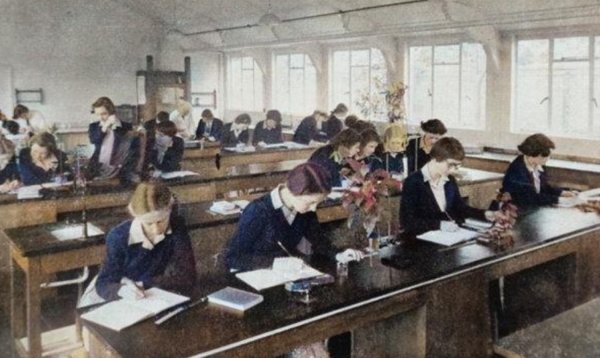

This colourised photograph was captioned 'Experiments in the new laboratory'.

From my

collection

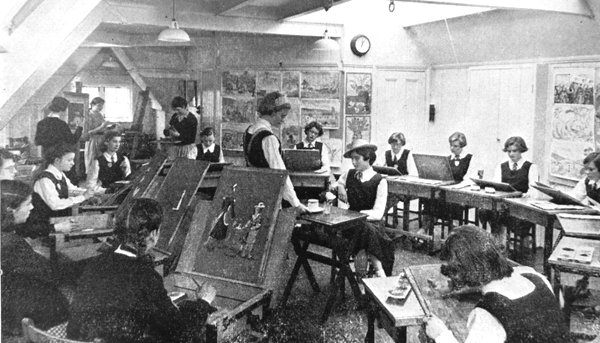

The art studio was once an attic. (I'm pretty sure I did an A-level Art History course here in the 1990s when it was part of Yeovil College).

From my

collection.

This

colourised photograph

features in my

book "Lost Yeovil"

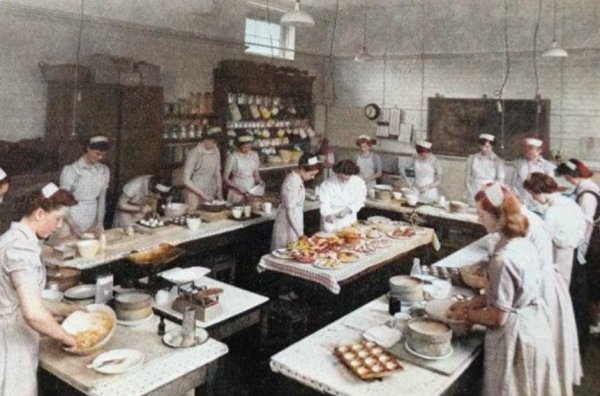

A colourised photograph of the General Certificate cookery class.

From my

collection

A colourised photograph of the Park Lodge garden.

From my

collection

The Beekeepers' Club. Members of the Club were prepared for the examinations of the Somerset Beekeepers' Association.

Many thanks to Patricia Ann Smith for the following - "Beekeeping was very interesting - better than lessons - especially extraction day. We dazed the bees with smokers, took out the wooden trays with the beeswax cells full of honey and took them over to the DS room at 45 The Park. We then used carving knives to cut the tops off the cells and slid the trays into a manual extractor (it looked like a Baby Burco Boiler) which had a handle on the top. We then turned the handle faster and faster so that centrifugal force forced the liquid honey out to trickle down the inside wall of the extractor. There was a tap at the bottom and we used it to pour the honey from it into jars. We also used to chew bits of the wax that we'd cut off the tops of the cells as it had some honey in it, and then chucked the chewed up bits down behind the Rayburn when Miss Greaves wasn't looking. Wonder if they're still there ....."