Spring Exhibition 2022

YEOVIL'S FASHIONS CAPTURED BY THE CAMERA

Spring Exhibition 2022 - presented by Yeovil's Virtual Museum

![]()

Photo by John Swatridge, c1860 |

|

![]()

About the Spring 2022 Exhibition

Today, of great value, is the recording of how ordinary Yeovilians looked and dressed through the decades. The vast legacy of cartes de visite and cabinet cards, followed by professionally-produced postcards and domestic photographs, have produced significant documentation of the fashions in clothing for both women and men.

This Spring 2022 Exhibition of Yeovil's Virtual Museum looks at the fashions of all classes of people in Yeovil from the 1850s to the 1920s. It should be borne in mind that a visit to the photographer’s studio, or even a home visit, would often have been a special occasion and called for the sitter to be attired in their ‘Sunday best’.

All photographs, except the 'glass chamber', are from my collection.

Introduction

Modern photography began in the late 1830s in France. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce used a portable camera obscura to expose to light a pewter plate coated with bitumen. This is the first recorded image that did not fade quickly.

The late 1840s saw the introduction of the photographic studio in England when the new 'science' of photography meant that a 'likeness' would soon become affordable for the masses. As with other towns, Yeovil saw its fair share of photographic artists setting up studios.

A typical photographer's 'glass chamber' |

|

In 1847, Thomas Sharp of London would become the first of several visiting professional photographers to set up temporary photographic studios in Yeovil, usually within existing shop premises. These temporary studios would exist for just a few weeks or several months - the ‘season’. Yeovil soon began to have more permanent studios created in the town. The first of Yeovil’s professional photographers was probably John Swatridge who, together with his son Thomas, set up a photographic studio in his shop premises in Princes Street during the 1850s. Since lighting for photography was a real problem at this time, the majority of the new studios, frequently called ‘glass chambers’, were little more than greenhouses equipped for photographic portraiture as seen at left. |

The next great

step forward in

photography was

the invention of

the carte de

visite, patented

in 1854 in

France by Andre

Adolphe Eugene

Disderi. The

carte de visite

image, or

images, were

usually taken in

multiples of

eight or less

and were small

enough for the

photographer to

take eight

images on a

whole plate

camera fitted

with four lenses

and a repeating

back. Most would

produce the same

image multiple

times but,

depending on the

camera and the

lens set-up,

some could

accommodate

various poses on

one photographic

plate.

Cartes de visite (also known as cartes or CDVs) are small paper-on-card photographs. The size of cartes quickly became standardised and they typically measure 4" x 2½" (102mm x 62mm). The photograph which was pasted on to the card was roughly cut to about 3½" x 2¼" (90mm x 57mm). They were never actually used as visiting cards.

Cartes de visite were introduced in Britain in 1859 and became a relatively cheap way for almost anyone to have their photograph taken. The newly-invented negative/positive process allowed photographers to easily produce multiple copies. This had not been possible with earlier photographic processes such as the ambrotype and the daguerreotype. By keeping the negatives, the photographer could offer reprints at any time after the initial sitting - a fact usually advertised on the back of the carte.

The ability to reproduce images in bulk, led to a fashion for Victorians to collect photographs of famous people, topographical views and a whole range of other subjects. This fashion was boosted in 1860 when the society photographer, JE Mayall, produced a set of photographs of the Royal family. As cartes became cheaper, people began to swap images with their friends and around 1870 leather-bound albums with bright brass clasps became popular. Until then, cartes had square corners, but these tended to rip the openings in albums. So, from around this time, cartes began to have rounded corners - an easy way to roughly date a carte.

Throughout the 1860s and 1870s the passion for collecting cartes boomed and literally millions were produced across the country each year. It has been called the start of ‘cartomania’.

Cabinet cards - a larger version of the carte - were introduced in 1866 by the London company of Window & Bridge to revitalise the flagging sales of cartes. However, they did not become really popular until the late 1880s and 1890s. Cabinet cards were the larger version of the carte de visite and customers were often sold the same photograph in both sizes. The photograph of a cabinet card measures 5½” x 4” (140mm x 100mm) and is pasted onto a mount measuring 6½” x 4¼” (165mm x 115mm). Cabinet cards usually have the studio name and address printed at the bottom.

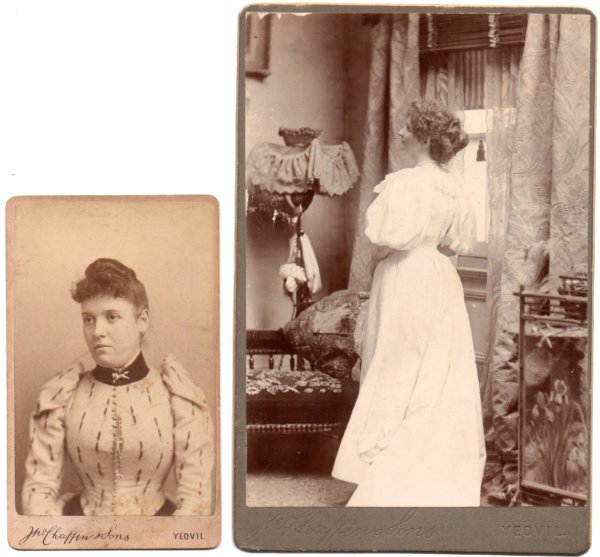

For size

comparison, at

left is a carte

de visite by

John Chaffin &

Sons of Hendford

(next door to

the Butchers

Arms), at right

is a cabinet

card also by

John Chaffin &

Sons, but

appears to be a

portrait taken

in the sitter’s

home. Both date

to the 1890s.

Cartes measure

approximately 4"

x 2½" (102mm x

62mm), while

cabinet cards

measure 6½” x

4¼” (165mm x

115mm).

The carte de visite format continued in use until around the turn of the twentieth-century, while the cabinet card persisted until about 1910. By this time, both had been replaced by the much cheaper postcard format.

As an example of the cost of a photograph - the visit to the studio was generally free and the following list of prices, from John Bell of Hendford in 1896, are typical -

-

Cartes de visite - 12 copies from 7 shillings (about £35 at today's value)

-

Cartes de visite - 6 copies from 4 shillings

-

Cartes de visite - 3 copies from 2s 6d

-

Re-orders - 6d each, any number

-

Cabinet Cards - 12 copies from 12 shillings

-

Cabinet Cards - 6 copies from 7s 6d

-

Cabinet Cards - 3 copies from 4s 6d

-

Re-orders - 1s each, any number

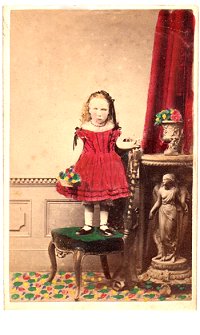

Many of the

early

photographers

had originally

trained as

artists and a

frequently-offered

service was to

provide a

coloured version

of the

photograph.

This was often

achieved by

creating a

portrait in

oils, or other

medium, as a

direct copy of a

photograph.

Alternatively,

as in this

example at left

(not a Yeovil

photographer), by

painting

directly onto

the photograph.

Many of the

early

photographers

had originally

trained as

artists and a

frequently-offered

service was to

provide a

coloured version

of the

photograph.

This was often

achieved by

creating a

portrait in

oils, or other

medium, as a

direct copy of a

photograph.

Alternatively,

as in this

example at left

(not a Yeovil

photographer), by

painting

directly onto

the photograph.

For example, John Chaffin of Hendford, employed his three daughters as artists to create lifelike portraits in oil paints or to colour monochrome prints. Louisa at the Hendford studio and at Taunton by her elder sisters Kate and Maria, who had earlier been listed as artists.

Fashions of the 1850s

Around 1856, skirts expanded creating a dome shape,

due to the

invention of the

artificial cage crinoline. The purpose of the crinoline was to create a

simulated

hourglass

silhouette by

accentuating the

hips and,

together with

the corset,

creating the

illusion of a

small waist. The

cage crinoline

was made from

thin strips of

metal, forming a

circular

structure to

support the

large width of

the skirt. The

introduction of

the crinoline

freed women from

the great weight

of many layers

of petticoats

and was a much

more hygienic

option.

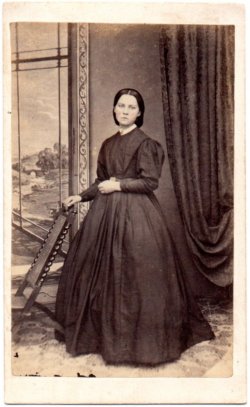

Proving

that

almost

anyone

could

afford a

carte de

visite,

this

carte de

visite

is of

Susan

Ellis

(1839-1903)

originally

from

Halstock,

Dorset,

who, in

the 1861

census

(three

years

after

the time

of this

photograph)

was

listed

as a

23-year

old

servant

living

with and

working

for the

family

of

bookseller,

stationer

and

printer

Henry Wippell

at

(today's)

1 & 3

Princes

Street.

Proving

that

almost

anyone

could

afford a

carte de

visite,

this

carte de

visite

is of

Susan

Ellis

(1839-1903)

originally

from

Halstock,

Dorset,

who, in

the 1861

census

(three

years

after

the time

of this

photograph)

was

listed

as a

23-year

old

servant

living

with and

working

for the

family

of

bookseller,

stationer

and

printer

Henry Wippell

at

(today's)

1 & 3

Princes

Street.

Susan's

dress is

typical

of the

mid- to

late-1850s

before

the full

crinoline

became

fashionable.

She holds a book - symbolising an educated young lady (as well as the fact that she worked for a bookseller). The background has a simple swag of material to one side and Coggan's ornate studio chair appears in many of his photographic portraits.

This older lady wears a dark silk morning crinoline dress

with the skirt

almost conical

and dressed

simply with

ruching around

the hem. The

sleeves are wide

and heavily

decorated.

This older lady wears a dark silk morning crinoline dress

with the skirt

almost conical

and dressed

simply with

ruching around

the hem. The

sleeves are wide

and heavily

decorated.

This lady's hair is dressed simply,

middle parted

and in a bun or

wound braid at

the back, with

the sides puffed

out over the

ears. She wears

an indoor cap

with long

ribbons which,

by this time,

was a little

dated and would

usually only

have been worn

by the older

generation.

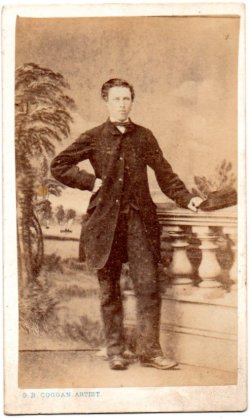

This

gentleman wears

a long frock

coat, for informal day wear, over a

straight cut,

single-breasted

waistcoat and

trousers of a

similar

material.

This

gentleman wears

a long frock

coat, for informal day wear, over a

straight cut,

single-breasted

waistcoat and

trousers of a

similar

material.

This photograph features a painted backdrop and the man rests on a moveable prop balustrade for stability during the photograph's exposure.

This lady has a similar dress to the previous photograph of the

older seated

lady. It has a high collar in contrasting white,

very full sleeves, a belt with a

large buckle at

the waist and

three layers of

frills at the

hem.

This lady has a similar dress to the previous photograph of the

older seated

lady. It has a high collar in contrasting white,

very full sleeves, a belt with a

large buckle at

the waist and

three layers of

frills at the

hem.

Her daughter wears a dress with a

design based on

adult’s

clothing. Like

her mother, she

has long dark

ribbons in her

hair.

Fashions of the 1860s

After about

1862, the

silhouette of

the crinoline

changed and

rather than

being

bell-shaped it

was now flatter

at the front and

projected out

more behind. In

men's fashion,

the sack coat

and cutaway

morning coat,

waistcoat, and

trousers in the

contrasting

fabric continued

as the norm.

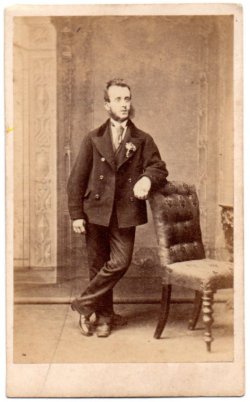

This

is the

earliest carte

by John Chaffin,

from 1862,

before Chaffin

started to have

the backs of his

CDVs printed (it

has a

hand-written

back).

This

is the

earliest carte

by John Chaffin,

from 1862,

before Chaffin

started to have

the backs of his

CDVs printed (it

has a

hand-written

back).

The sitter’s

early style sack

coat is typical

of this period.

The sack suit,

or lounge suit

as it was termed

in Great

Britain,

originated in

France as the sacque

coat during the

1840s and took

its name from

the way it was

cut (contrary to

popular belief,

the sack coat

did NOT get its

name from its

loose fit “like

a sack”).

The full length

portrait was

normal during

this period,

with clear areas

of floor visible

below the

sitter. The

background is

quite plain and

the props are

sparse. Note the

base of a neck

clamp behind the

sitter’s feet.

Neck clamps were

used in order to

stop the

sitter’s head

moving.

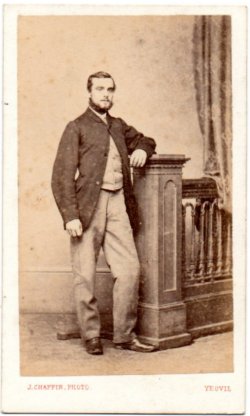

Again,

one of the very

earliest cartes

de visite by

John Chaffin,

almost certainly

dating to 1862.

In this

instance,

Chaffin had

bought a

standardised

carte with a

printed back

with name and

address

hand-written

indicating that

he had still yet

to organise the

printing of his

own carte

stocks.

Again,

one of the very

earliest cartes

de visite by

John Chaffin,

almost certainly

dating to 1862.

In this

instance,

Chaffin had

bought a

standardised

carte with a

printed back

with name and

address

hand-written

indicating that

he had still yet

to organise the

printing of his

own carte

stocks.

For most of the nineteenth century children's clothes were all but replicas of their parents fashions, the exception being that young girls' dresses were shorter than adults.

The same painted

backdrop as in

the next

photograph is

seen, featuring

a rural

landscape. The

balustrade prop,

for support

during the long

photographic

exposure, was

appropriately

short for the

use of children,

although as seen

at the left edge

clearly isn't

long enough to

be convincing.

Another

very early carte

by John Chaffin

from around

1862, featuring

the lady’s

dress, with its

full,

bell-shaped

crinoline

skirts, typical

of this date.

The fashion

would change

dramatically

within a year or

two.

Another

very early carte

by John Chaffin

from around

1862, featuring

the lady’s

dress, with its

full,

bell-shaped

crinoline

skirts, typical

of this date.

The fashion

would change

dramatically

within a year or

two.

Her hair style, centre-parted and swept back showing her ears is another indicator of this period.

The same painted backdrop as in the previous photograph is seen again. It was typical of the period and shows a simplified opening with a view through to the outside.

The balustrade

studio prop, on

which the lady

rests was

moveable and

features in many

of Chaffin's

studio portraits

for many years.

This

man, also

photographed by

Chaffin in 1863,

wears a

tailored,

mid-thigh length

morning coat

that tended to

be worn for more

formal day

occasions.

This

man, also

photographed by

Chaffin in 1863,

wears a

tailored,

mid-thigh length

morning coat

that tended to

be worn for more

formal day

occasions.

The morning coat was cutaway, as here, so that only the top button could be fastened. It was ideal for business wear. Waistcoats, usually in a contrasting, plain material, were generally cut straight across the front and had lapels. He wears traditional contrasting light-coloured trousers.

The props are a

simple swag of

material and the

moveable

balustrade makes

another

appearance.

Note behind the

the man’s legs

are the feet of

a neck brace to

keep him from

moving his head

during the long

exposure time.

Fashions of the 1870s

1870's fashion

is characterised

by a gradual

return to a

narrow

silhouette after

the full-skirted

fashions of the

1850s and 1860s.

By 1870,

fullness in the

skirt had moved

to the rear,

where

elaborately-draped

overskirts were

supported by a

bustle and

secured by

tapes. This

necessitated an

underskirt,

which was

heavily trimmed

with pleats,

ruching, and

frills. The

bustle was

short-lived at

this time,

although it

would return

again in the

mid-1880s. It

was followed by

a tight-fitting

silhouette. The

cuirass bodice,

a long-waisted,

boned bodice

extending into a

point below the

waistline in

both front and

back. Sleeves

were very tight

fitting. Square

necklines were

common and day

dresses had high

necklines that

were either

closed, squared,

or V-shaped.

Sleeves of

morning dresses

were narrow

throughout the

period and women

often draped

overskirts to

create an

apron-like

effect from the

front.

Typical

of the early

1870s, this

lady's day dress

is quite simple

and fairly

plain. The high

neckline of the

buttoned bodice

(the buttons

appear to be the

same colour as

the dress

fabric, while

the four white

'buttons' are,

in fact, a

jewellery

ornament).

Typical

of the early

1870s, this

lady's day dress

is quite simple

and fairly

plain. The high

neckline of the

buttoned bodice

(the buttons

appear to be the

same colour as

the dress

fabric, while

the four white

'buttons' are,

in fact, a

jewellery

ornament).

The skirts are now much reduced and are flatter at the front, with an emphasis at the rear. In the following years the rear 'emphasis' would be enhanced by the use of a bustle.

Of particular

interest is the

chair featured.

This is not a

normal chair,

but a

photographer's

'posing' chair.

This was

designed such

that the 'seat'

could be used

for sitting or

kneeling and the

height of both

the seat and the

padded back

would have been

fully

adjustable, to

accommodate

sitters of

different

heights.

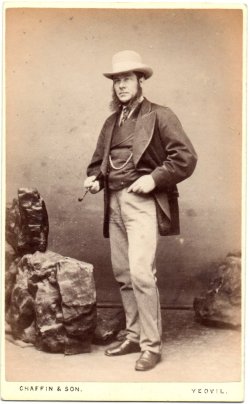

This

photograph by

John Chaffin dates to

1870.

This

photograph by

John Chaffin dates to

1870.

The man, in what is sometimes referred to as a promenade suit, wears a long jacket with very wide lapels and generous sleeves - a refinement of the earlier sack coat.

He wears a collar and silk tie, with a jewelled tie pin through the tie's knot.

His waistcoat, worn with a heavy watch chain, is double breasted and of the same material. It is worn with contrasting light coloured trousers (they are actually finely striped). The ensemble is finished off with a summer hat and a cane.

The scene is somewhat let down by a plain background and incongruous papier-mâché rocks.

In

Britain the

return of the

beard (the full

beard had last

been in vogue in

Tudor times) was

thanks to the

Crimean War of

1854-56. Beards

had been banned

in the British

army until this

time, but the

freezing

temperatures of

Crimean winters,

and the

impossibility of

getting shaving

soap, led to a

necessary

change. By the

time the last

troops returned

home, beards

were the mark of

a hero. Within a

few years, it

was almost

impossible to

see a beard-free

male face in

Victorian

Britain. During

the 1860s and

'70s, Piccadilly

weepers , or as

the Americans

called them,

Dundreary

whiskers, became

popular. They

were long bushy,

carefully combed

side whiskers,

worn without a

beard.

In

Britain the

return of the

beard (the full

beard had last

been in vogue in

Tudor times) was

thanks to the

Crimean War of

1854-56. Beards

had been banned

in the British

army until this

time, but the

freezing

temperatures of

Crimean winters,

and the

impossibility of

getting shaving

soap, led to a

necessary

change. By the

time the last

troops returned

home, beards

were the mark of

a hero. Within a

few years, it

was almost

impossible to

see a beard-free

male face in

Victorian

Britain. During

the 1860s and

'70s, Piccadilly

weepers , or as

the Americans

called them,

Dundreary

whiskers, became

popular. They

were long bushy,

carefully combed

side whiskers,

worn without a

beard.

1870's

fashion is

characterised by

a gradual return

to a narrow

silhouette after

the full-skirted

fashions of the

1850s and 1860s.

By 1870,

fullness in the

skirt had moved

to the rear, and

here

elaborately-draped

overskirts were

supported by a

bustle and

secured by

tapes. This

necessitated an

underskirt,

which was

heavily trimmed

with pleats,

ruching, and

frills.

1870's

fashion is

characterised by

a gradual return

to a narrow

silhouette after

the full-skirted

fashions of the

1850s and 1860s.

By 1870,

fullness in the

skirt had moved

to the rear, and

here

elaborately-draped

overskirts were

supported by a

bustle and

secured by

tapes. This

necessitated an

underskirt,

which was

heavily trimmed

with pleats,

ruching, and

frills.

Of special interest is the early use of an elaborately painted 'outdoor' backcloth (the like of which had not been seen for a decade) and the massive 'rock' (probably Papier-mâché) posing aid on a wooden base. It is likely that Chaffin's daughters, who were all artists, painted the backcloth and possibly created the impressive 'rock'.

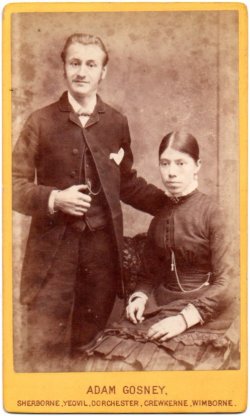

Photographed

in the

late-1870s

by

Adam Gosney

of Sherborne.

Gosney

had a

studio in

Princes Street, as well as Sherborne, Dorchester, Crewkerne and Wimborne.

Gosney also

invested in a

mobile

photographic

studio with

which he

travelled to

many villages

throughout the

district.

Photographed

in the

late-1870s

by

Adam Gosney

of Sherborne.

Gosney

had a

studio in

Princes Street, as well as Sherborne, Dorchester, Crewkerne and Wimborne.

Gosney also

invested in a

mobile

photographic

studio with

which he

travelled to

many villages

throughout the

district.

This lady’s skirts are trimmed with layers of ruching. The sleeves are tight and the cuffs edged with white lace to match that at the high collar. Her hair is severely pulled back.

The man wears a thigh-length cutaway jacket, with tiny lapels, buttoned at

the top, over a

single-breasted

waistcoat.

For the first time we do not see an expanse of carpet below the sitters' feet.

This

carte, also by

Chaffin, dates

to around 1874.

This

carte, also by

Chaffin, dates

to around 1874.

The lady’s bustled dress with its overskirts, is a style that became fashionable around 1873 to 1874 and featured overskirts and an apron-like overskirt, caught up with buckled ribbons. Again, the bustle emphasises the rear of the skirts.

The bodice is of the 'Cuirassier' style with a drop-pointed front, plainly decorated and with quite tight sleeves with button detailing.

Unusually for a photograph at this date, the lady wears large pendulous earrings.

The props are minimal, with the edge of a fringed table supporting a book - the ever-present symbol of education.

Fashions of the 1880s

Ladies' fashion in the middle of the 1880s was characterised by the return of the bustle as emphasis remained on the back of the skirt. The long, lean line of the 1870s was slowly replaced by a full, curvy silhouette with gradually widening shoulders. Fashionable waists were low and tiny below a full, low bust supported by a corset.

As

in the previous

decade, emphasis

remained on the

back of the

skirt, with

fullness

gradually rising

from behind the

knees to just

below the waist.

The fullness

over the bottom

was balanced by

a fuller, lower

chest, achieved

by rigid

corseting,

creating a

narrow waist and

an S-shaped

silhouette.

As

in the previous

decade, emphasis

remained on the

back of the

skirt, with

fullness

gradually rising

from behind the

knees to just

below the waist.

The fullness

over the bottom

was balanced by

a fuller, lower

chest, achieved

by rigid

corseting,

creating a

narrow waist and

an S-shaped

silhouette.

These gowns typically did not have a long train in the back, which was different from the gowns worn in the 1870s, and were extremely tight. They did still have overskirts. They were known as the "hobble-skirt" due to the tightness of them.

The painted backdrop is 'rustic' and flowers / foliage in the foreground help to give the illusion that the lady is outside, in the countryside.

This

lady's velvet

dress emphasises

her tiny

corseted waist

with a draped

overskirt and

bustle. The

effect is

accentuated by

focusing

attention on her

bosom and hips -

producing the

ideal full,

curvy

silhouette.

This

lady's velvet

dress emphasises

her tiny

corseted waist

with a draped

overskirt and

bustle. The

effect is

accentuated by

focusing

attention on her

bosom and hips -

producing the

ideal full,

curvy

silhouette.

Her high collar trimmed with white lace, a carry-over from the previous decade, is typical of the early 1880s.

The background is extremely plain - unusual for this period.

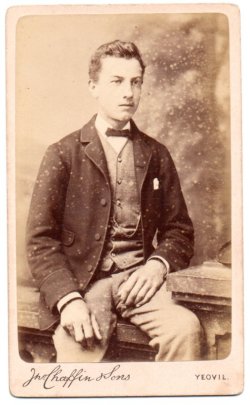

A

good

three-quarters

shot of a young

man seated on a

prop balustrade

in front of a

rural backcloth.

A

good

three-quarters

shot of a young

man seated on a

prop balustrade

in front of a

rural backcloth.

He wears a

tailored jacket,

far less loose

than the earlier

sack coat, with

a high-buttoned,

single breasted

contrasting

waistcoat and

trousers of the

same

finely-striped

material. He

wears a bow tie.

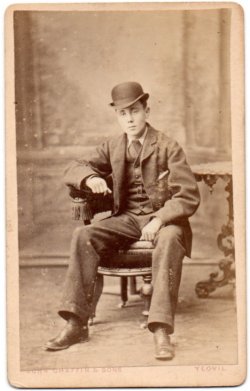

The

man in this

carte wears a

three piece suit

with jacket,

waistcoat and

trousers all in

matching

material (called

a ‘ditto suit’)

and sports a

bowler hat -

traditionally

worn with

informal attire

and favoured by

the working

classes.

The

man in this

carte wears a

three piece suit

with jacket,

waistcoat and

trousers all in

matching

material (called

a ‘ditto suit’)

and sports a

bowler hat -

traditionally

worn with

informal attire

and favoured by

the working

classes.

The man sits on the photographer's adjustable 'posing' chair, and the base of a head support is clearly seen behind the legs of the chair.

The use of props is again sparse.

During the Victorian age, different style clothing was worn according to age and gender. Girls wore mostly skirts and dresses, the style and length changed as they grew older. Meanwhile, the boys wore sailor suits, and clothes that would be considered girls clothes in modern standards.

Girl’s fashion from the Victorian era was mostly based on skirts. At certain ages, the skirts would have to be longer. At first, before they started school, the girls would wear very frilly dresses - the frillier the dress, the richer the family. When they got into school, then they would usually wear skirts. The skirts would start at about knee level, at ten years of age the hemline would drop to about mid-calf, and at sixteen years of age they would go all the way down to their ankles. At this age, the girls started dressing more like adults - even wearing corsets underneath their clothes, to make their bodies look the way that was most popular then.

Boys would also

commonly dress

according to

their age. They

would usually

wear

knickerbockers

as a standard,

casual piece of

clothing. Very

young boys wore

frocks, blouses,

and tunics with

pleated skirts

up until the age

of three or four

(I even have a

photo of my

three-year-old

grandfather in a

dress in 1902).

After this young

age, they wore

knickerbockers

with short,

collarless

jackets. Boys

also wore the

popular

naval-style

uniform, or

'sailor suit',

which consisted

of buttoned

trousers, dark

stockings, black

boots, buttoned

reefer jackets,

and a wide brim

straw hat. Most

of the

naval-style

clothing was

either colored

in white, black,

or navy blue.

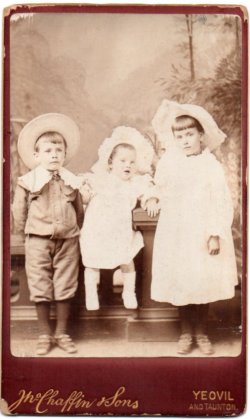

Unlike

in the 1860s

(q.v.), by the

end of the 1880s

children's

clothes were no

longer little

replicas of

their parents'

wardrobes.

Unlike

in the 1860s

(q.v.), by the

end of the 1880s

children's

clothes were no

longer little

replicas of

their parents'

wardrobes.

The children’s

clothes in this

carte are

typical of this

period. The

little girls

wear

loose-fitting

white smock-type

dresses with sun

bonnets. Girls

dresses

continued to be

much shorter

than adults'

hemlines.

The little boy

wears

knickerbockers,

a shirt with a

very large

Oxford collar

and a large sun

hat.

This carte is a

deluxe version

with a

maroon-coloured

stock sporting a

gold edge and

gold lettering.

Note that the front is printed “Yeovil and Taunton” after Chaffin opened his Taunton studio that would eventually be run by his son..

Fashions of the 1890s

Fashionable women's clothing styles shed some of the extravagances of previous decades, so that skirts were neither supported by crinolines as in the early 1860s, nor protrudingly bustled in back as in the late 1860s and mid-1880s, or tight as in the late 1870s. Nevertheless, corseting continued unmitigated, or even slightly increased in severity.

Early 1890's dresses generally consisted of a tight bodice with the skirt gathered at the waist and falling more naturally over the hips and undergarments than in previous years. The 1890s introduced 'leg of mutton' sleeves, which grew in size each year until they disappeared around the end of 1896.

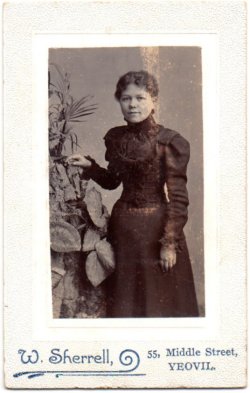

This

is a special

deluxe carte de

visite with the

photograph,

smaller than

normal, set

within an

embossed border.

It is by

William Sherrell.

This

is a special

deluxe carte de

visite with the

photograph,

smaller than

normal, set

within an

embossed border.

It is by

William Sherrell.

The carte dates to the early 1890s, as evidenced by the nascent ‘leg of mutton’ sleeves of the sitter which were tight for most of the length of the arm, but enlarged at the top of the arm.

The dark-coloured day dress is decorated with much lace to the bodice, the sleeve cuffs and the high collar.

Shutter speeds were improving at this time but exposures were still relatively long, so the lady has an ornate pillar, decorated with house plants, with which to steady herself.

Dating

to around 1895,

this magnificent

dress features

enormous 'leg of

mutton' sleeves

- without doubt

the most extreme

example of this

five-year

fashion in which

sleeves

increased

annually in size

until the

fashion faded in

1896.

Dating

to around 1895,

this magnificent

dress features

enormous 'leg of

mutton' sleeves

- without doubt

the most extreme

example of this

five-year

fashion in which

sleeves

increased

annually in size

until the

fashion faded in

1896.

It is difficult to tell if the bodice and skirt are separate items, but nevertheless the lower half of the bodice is in the same fabric as the skirt. Again, a rigid corset produces a tiny waist while emphasising the bosom.

Again, the lady balances herself on Sherrell's prop column, this time adorned with ferns. There is also a large rural backdrop.

This is a fine deluxe carte de visite, with a plain dark brown back and gold lettering and edging on a heavy cardstock. This is probably one of the last cartes by Chaffin & Sons before they moved to the postcard format.

Dating to around 1895, the lady wears a tailored jacket with exaggerated leg of mutton sleeves, a massive collar and a small dead animal.

Her hair is piled up on top of her head and her hat sits high and straight, trimmed with feathers.

Her skirt appears to be the popular simple A-line of the time.

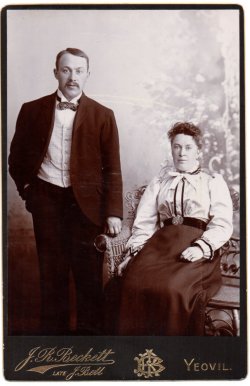

This

photograph, by

Jarrett Beckett,

was produced as

a cabinet card

and dates to

about 1898.

This

photograph, by

Jarrett Beckett,

was produced as

a cabinet card

and dates to

about 1898.

The lady wears a silky, striped blouse with generous, residual ’leg of mutton’ sleeves and is decorated with ribbons and lace at the high collar and cuffs. Her skirt is dark and plain, in contrast to her blouse.

The man wears a three-piece suit with matching coat and trousers but a contrasting, chequered waistcoat. Waistcoats fastened lower on the chest, and were collarless.

His shirt collar is turned over into "wings" - collars were overall very tall and stiffened. He wears a fashionable fancy bow tie.

Fashions of the 1900s

The fashionable silhouette in the early twentieth century was that of the 'confident woman', with full low chest and curvy hips. The 'health corset' of this period removed pressure from the abdomen and created an S-curve silhouette. Early twentieth century blouses and dresses were full in front and puffed into a 'pigeon breast' shape over a narrow waist. Skirts still brushed the floor, even for day dresses, in mid-decade.

For men, the long, lean, and athletic silhouette of the 1890s persisted.

By this time, the carte de visite was little used and the cabinet card was in sharp decline, both being replaced by the new postcard format, enabling photographs - whether they be professionally taken or by enthusiastic amateurs - to be sent to friends and loved ones.

This

is a photograph

of four sisters

produced as a

postcard around

1905.

This

is a photograph

of four sisters

produced as a

postcard around

1905.

The girls all wear similar, but slightly different, dresses. Girls generally wore their dresses shorter than adults and the younger the girl, the shorter the dress.

Note that the eldest (seated) girl wears a wristwatch. Wristwatches were worn only by women before the twentieth century - and more for decoration rather than anything as practical as punctuality.

20-year-old

Ellen Warren

photographed in

1909 (and

produced as a

cabinet card,

despite the late

date) in her

wedding dress.

20-year-old

Ellen Warren

photographed in

1909 (and

produced as a

cabinet card,

despite the late

date) in her

wedding dress.

The full-length dress is in a slimming, dark navy, square-cut at the neck but with a white lace, high collar infill. The dress has the smallest of lace cuffs in very tight sleeves, with silk detailing at the elbows matching the detailing across the line of the bosom. The lower sleeves are in a colour-matched crepe.

Her hair style is typical of the Edwardian period.

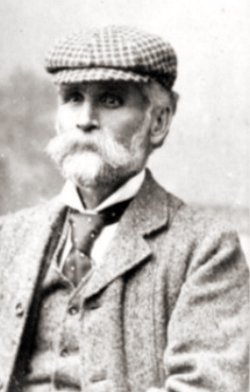

The

Norfolk jacket,

made of sturdy

tweed or similar

materials,

gained

popularity for

rugged outdoor

pursuits, such

as fishing and

shooting.

The

Norfolk jacket,

made of sturdy

tweed or similar

materials,

gained

popularity for

rugged outdoor

pursuits, such

as fishing and

shooting.

It would be worn with matching waistcoat and breeches, when it became the Norfolk suit, suitable for bicycling or golf with knee-length stockings and low shoes.

The man wears a winged collar with a necktie. The flat cap was commonly worn at this time by all classes.

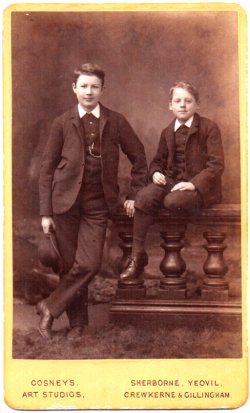

Again

photographed by

Adam Gosney, but

in the carte de

visite format

that had been

abandoned by

most other

photographers.

Again

photographed by

Adam Gosney, but

in the carte de

visite format

that had been

abandoned by

most other

photographers.

These two boys wear suits that would have emulated their father's.

The waistcoats are fastened high on the chest. The usual style, as here, was single-breasted.

The older boy, standing, wears a watch chain and carries a bowler hat while his younger brother wears knickerbocker trousers because of his age.

Fashions of the 1910s

Fashion from 1910–1919 was characterised by a rich and exotic opulence in the first half of the decade in contrast with the sombre practicality of garments worn during the Great War period. Men's trousers were worn cuffed to ankle-length and creased. Skirts rose from floor length to well above the ankle by the end of the decade. Women began to bob their hair, and the stage was set for the radical new fashions associated with the Jazz Age of the 1920s.

High Street decorated to celebrate the Coronation of George V on 22 June 1911. The ladies at left and right have ankle-length hemlines, but the five younger girls at centre have higher hemlines because of their age. Nearly all the ladies and girls wear fashionable wide-brimmed hats.

This

photograph dates

to about 1910.

This

photograph dates

to about 1910.

Large hats with wide brims and broad hats with face-shadowing brims were the height of fashion in the early years of the decade, gradually shrinking to smaller hats with flat brims.

Fur muffs and stoles were important fashion accessories in this period.

Beneath her coat this young lady wears a separate blouse and skirt; the blouse has a high frilly collar while the skirt length is just a couple of inches clear of the ground.

This

studio portrait

is by

Grace Cumming,

who was only

active as a

photographer in

Yeovil in 1911

and 1912. Grace

died in 1913.

This

studio portrait

is by

Grace Cumming,

who was only

active as a

photographer in

Yeovil in 1911

and 1912. Grace

died in 1913.

Produced as a postcard, it is embossed with Grace's name at the bottom right corner.

By this time the man’s double-breasted jacket has morphed from the earlier sack coat to become the modern suit jacket. He wears matching trousers and probably wears a matching waistcoat.

The background is a simple swag of material.

During

the 1914-1918

War, the vast

majority of

men’s clothing

naturally tended

to be military

in nature.

During

the 1914-1918

War, the vast

majority of

men’s clothing

naturally tended

to be military

in nature.

This corporal had his photograph taken while on leave.

It was usual for servicemen to have a photographic portrait as a keepsake for their loved ones while they were away on active service. These are more numerous today than any other type of portrait of this decade.

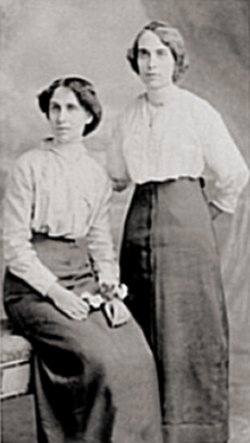

This

photograph of

two sisters

dates to about

1917 and shows

the very plain

style that

became popular

during the Great

War.

This

photograph of

two sisters

dates to about

1917 and shows

the very plain

style that

became popular

during the Great

War.

Both ladies wear simple long-sleeved blouses with high necks with ankle-length plain skirts.

These are the two elder sisters shown in the photograph of the four sisters of 1905 above.

Fashions of the 1920s

The 1920s was the decade in which fashion entered the modern era. It was the decade in which women first abandoned the more restricting fashions of past years (the confining corset was discarded by most) and began to wear more comfortable clothes.

The decade was characterised by two distinct periods of fashion. In the early part of the decade, change was slow, as many were reluctant to adopt new styles. From 1925, the public passionately embraced the styles associated with the Roaring Twenties.

Men also generally abandoned highly formal daily attire and even began to wear athletic clothing for the first time. The suits men wear today are still based, for the most part, on those worn in the late 1920s.

Photographed

by

Witcomb & Son

around 1924, and

produced as a

postcard.

Photographed

by

Witcomb & Son

around 1924, and

produced as a

postcard.

This lady, with her bobbed hair, wears a drop-waisted dress with a loose, straight fit and shorter sleeves.

Although unseen in this photograph, the length of her dress would be just below the knees.

Further, she is unencumbered by the rigid corsetry of previous decades.

By

1920 the

'bobbed' hair

style was

rapidly becoming

fashionable

although in the

early 1920s it

was still seen

as a somewhat

shocking

statement of

independence in

young women, as

older people

were used to

seeing girls

wearing long

dresses and

heavy

Edwardian-style

hair.

Hairdressers,

whose training

was mainly in

arranging and

curling long

hair, were slow

to realise that

short styles for

women had

arrived to stay.

The bobbed style

became standard

by the end of

the decade.

By

1920 the

'bobbed' hair

style was

rapidly becoming

fashionable

although in the

early 1920s it

was still seen

as a somewhat

shocking

statement of

independence in

young women, as

older people

were used to

seeing girls

wearing long

dresses and

heavy

Edwardian-style

hair.

Hairdressers,

whose training

was mainly in

arranging and

curling long

hair, were slow

to realise that

short styles for

women had

arrived to stay.

The bobbed style

became standard

by the end of

the decade.

This young lady wears the most iconic 1920s coat, the fur collar wrap coat, or 'cocoon coat'. This was a woman’s prized possession. Almost every woman owned one and wore it throughout the year.

This

formal family

group photograph

dates to 1928

and shows a

range of 'Sunday

best' clothing.

This

formal family

group photograph

dates to 1928

and shows a

range of 'Sunday

best' clothing.

For the first time in centuries, women's legs were seen with hemlines rising almost to the knee and dresses becoming more fitted.

The cloche hat was a fitted, bell-shaped hat for women that was invented in 1908 but became especially popular from about 1922 to 1933.

Although the younger lads wear a standard 'newsboy' cap and a flat cap, these were also popular with working class men at this time - as were the trilby hats worn here by the older men.

The

ever popular

'box brownie'

camera (invented

in 1900) allowed

people to take

their own

photographs at

any location as,

for example,

this scene on a

crowded beach.

The

ever popular

'box brownie'

camera (invented

in 1900) allowed

people to take

their own

photographs at

any location as,

for example,

this scene on a

crowded beach.

While the older ladies at left retain their somewhat old-fashioned clothes and hats, the young couple have a far more relaxed wardrobe - an open shirt collar (albeit still with a double-breasted suit jacket buttoned up, even on the beach).

Even the older man has removed his stiff shirt collar for the occasion.