Yeovil at War

Camouflaging Yeovil

Hiding the town and the Westland aircraft factory from Nazi bombers

Even during the early 1930s with the prospect of war on the far horizon, there was concern that in such a war, bombing of strategic installations such as airfields would become a huge problem. The chief concern was for the appearance of airfields and associated buildings as seen from the air. In 1935 the Air Ministry Director of Works emphasized to the Air Staff the absence of any policy for concealment and camouflage of RAF establishments at home.

A General Camouflage Policy was developed in 1938, the aim being to treat, in a practical and economical manner, the distinctive features of an RAF station: buildings, landing grounds, boundaries etc. – so that an enemy pilot would be deceived or confused. It was assumed that the main purpose of airfield camouflage would be achieved if recognition of a target could be delayed, so preventing an attack, or at least causing it to be inaccurate.

Progress was slow, and it was not until 1940 that all three branches of the services had formed camouflage branches. In 1940 the Camouflage Development and Training Centre (CDTC) was established at Farnham Castle in Surrey with the purpose of developing and teaching military camouflage techniques. The centre recruited artists such as Freddy Gore, who later became a Royal Engineers Camouflage Officer based in the south east, and Roland Penrose, a Quaker pacifist who later taught military camouflage at the Osterley Park training centre for the Home Guard and wrote the 'Home Guard Manual of Camouflage'. He became Senior Lecturer at the Eastern Command Camouflage School in Norwich, set up by Oliver Messel - also a Royal Engineers Camouflage Officer who is known to have worked on camouflaging pillboxes in Somerset in 1940. Another early member of the CDTC was the stage illusionist Jasper Maskelyne, later famous for his use of innovative illusions in North Africa to create the likes of fake tanks and buildings and, in his pièce de résistance, even concealing Alexandria and the Suez Canal from German bombers.

The General Camouflage Policy had two main objectives: firstly, to break up the regularity and conspicuousness of the buildings; and secondly, to break up the airfield into a pattern more closely resembling the surrounding countryside.

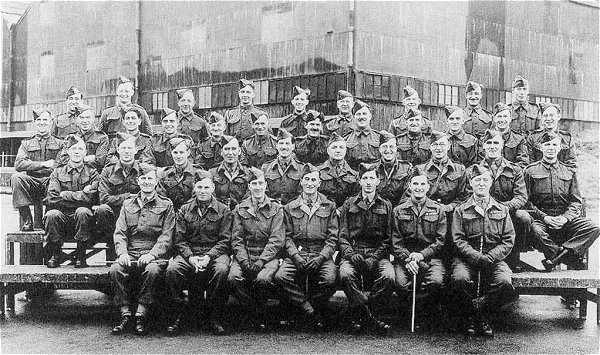

At Yeovil the first objective was attempted by painting irregular, differently coloured, patches on the walls and roofs of buildings and surrounding ground and also trying to break up the outline of large buildings by painting them to look like smaller residential houses - as shown in the first three photographs below. The first shows a group photograph of Officers and Sergeants of Westlands Company, Home Guard, posing in front of the erecting shop in the background, painted in a camouflage design that attempted to make it look like residential buildings. The second photograph shows how effective the camouflage painting of buildings could be when seen from the air. The third example shows surviving camouflage paint on the old Gaumont Palace that was again camouflaged by painting it to look like residential buildings.

As for the airfield itself, the grass of the airfield was treated with heavy lines of creosote and oil which, when seen from the air, made the airfield appear as a number of small fields - as shown in the final three photographs.

This General Camouflage Policy remained in force until it was discontinued in 1944.

See also Yeovil's Starfish Site, SF42

gallery

Officers and Sergeants of Westlands Company, Home Guard. Note the painted camouflage on the erecting shop in the background, attempting to make it look like residential buildings.

A wartime aerial photograph of the Westland aircraft factory buildings with camouflage paint applied. Note especially the large building at bottom left, very effectively disguised as a row of semi-detached houses.

A slightly different view of the large hangar camouflaged to represent three pairs of semi-detached houses. Even the front gardens and paths are painted in perspective up the lower part of the wall.

During the Second World War the Gaumont Palace was camouflaged by painting it to look like residential buildings. The camouflage remains to this day on the southern elevation facing Summerhouse Hill as seen in this photograph taken in 2013.

Courtesy of

Yeovil Library

This is part of a German reconnaissance photograph of the Second World War highlighting the targets of Westland's Airfield (marked 'A'), a temporary army camp (marked 'B') and the Westland factory (marked 'C'). Within 'A' are three aircraft hangers marked '1' in the lower right corner and the airfield itself is marked '2' - note how the airfield has been camouflaged by pouring oil on the grass to create the appearance of hedges around small fields. Within 'B', essentially Houndstone and Lufton camps, are several barracks huts, each marked '3'. Dotted around the map and marked '4' are several sites of 'Fesselballons' or barrage balloon sites.

A grainy wartime aerial photograph of the Westland airfield, covering pretty much the whole of the centre of the photograph, but disguised as a number of small fields with oil poured on the grass to look like field boundary hedges.

An aerial photograph of Westlands taken in 1941 with three barrage balloons circled in red. The main airfield has been visually broken up with oil and creosote poured onto the grass to form 'hedges' and visually breaking up the large mass of the airfield.