yeovil at War

Arthur James Cook

Died of wounds sustained on the Western Front

Arthur James Cook was born in Yeovil in 1881, the son of painter and decorator Albert Cook (b1842) of Yeovil and Emma Jane née Cook (1849-1908) originally of Chard. Albert and Emma lived in Yeovil with their two sons Frederick (b1871) and Arthur but had moved to Bourne Valley, Parkstone, Dorset, by the time their daughters Ethel (b1885) and Evelyn (b1888) were born. The family were still at Parkstone in the 1901 census; Albert gave his occupation as a house painter, Emma was a laundress and 20-year old Arthur was employed as a bricklayer's labourer.

In 1908 Emma died and in the 1911 census Albert, Arthur, Ethel and Evelyn were listed at Honeysuckle Villa, Solby Road, Parkstone. By this time Albert had retired and Arthur was working as a contractor's labourer.

Arthur

enlisted as a

Private in the

Duke of

Cornwall's Light

Infantry at

Holton,

Somerset. It

is not known

when he

enlisted, but

his Service

Number 24951

suggests it was

at the beginning

of 1916.

Arthur

enlisted as a

Private in the

Duke of

Cornwall's Light

Infantry at

Holton,

Somerset. It

is not known

when he

enlisted, but

his Service

Number 24951

suggests it was

at the beginning

of 1916.

However, it appears that within a very short space of time he was transferred to the newly-formed 34th (Labour) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers. The battalion was formed at Falmer in June 1916 and it is most likely that Arthur was transferred at this time. His new Service Number was 60091.

In April 1917, a number of Infantry battalions were transferred to the Labour Corps. The Labour Corps absorbed the 28 ASC Labour Companies between February and June 1917. In April 1917 the 34th (Labour) Battalion, including Arthur, became the 101st Labour Company, Labour Corps.

The Labour Corps grew to some 389,900 men (more than 10% of the total size of the Army) by the Armistice. Of this total, around 175,000 were working in the United Kingdom and the rest in the theatres of war.

The Corps was manned by officers and other ranks who had been medically rated below the 'A1' condition needed for front line service and many were returned wounded. Labour Corps units were often deployed for work within range of the enemy guns, sometimes for lengthy periods.

Although the army in France and Flanders was able to use some railways, steam engines and tracked vehicles for haulage, the immense effort of building and maintaining the huge network of roads, railways, canals, buildings, camps, stores, dumps, telegraph and telephone systems, etc, and also for moving stores, relied on horse, mule and human.

The labour units expanded hugely and became increasingly well-organised. However, despite adding large numbers of men from India, Egypt, China and elsewhere, there was never enough manpower to do all the labouring work required. The total number of men engaged on work in France and Flanders alone approximated 700,000 at the end of the war, and this was in the labour units alone. In many cases the men of the infantry, artillery and other arms were forced to give up time to hard effort when perhaps training or rest might have been a more effective option.

In the crises of March through April 1918 on the Western Front, Labour Corps Units were used as emergency infantry. It is most likely that Arthur was among their number as we know he was wounded on the Western Front. He was transported back to England where he died of his wounds on 22 May 1918. He was 36 years old.

Arthur was buried in Brookwood Military Cemetery, Surrey, England, Grave XIII.D.10A. His name was added to the War Memorial in the Borough in 2018.

gallery

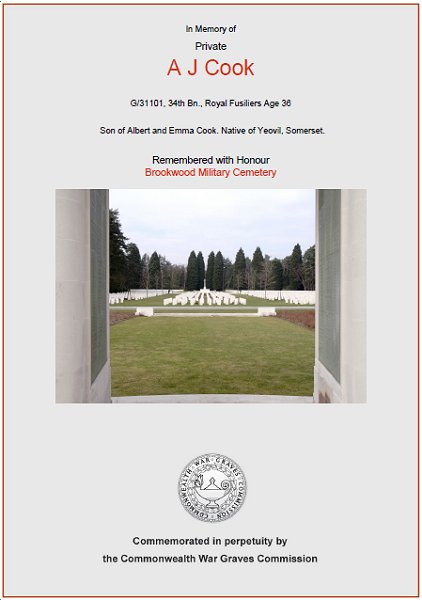

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission certificate in memory of Arthur Cook.

Arthur Cook's headstone.