yeovil people

Henry Pitman

Took part in the Monmouth Rebellion, tried by Judge Jeffreys at the 'Bloody Assizes', transported, escaped, had adventures with pirates, returned to England and became the inspiration of the 1935 Errol Flynn movie 'Captain Blood'

Henry Pitman was born around 1655. His parents were of the lower gentry class and Quakers; William Pitman of Sandford Orcas and his wife Gertrude née Lavor, the daughter of John and Mary Lavor of Yeovil. William's uncle, was Henry Lavor, who was active in the Quaker community from its inception in Yeovil, with the Quakers meeting in Henry Lavor’s house in Yeovil from 1654. One of his brothers-in-law was Elias Barnes (married to his sister Mary) who was a Yeovil maltster and early Yeovil Congregationalist. Another brother-in-law was Yeovil glover Samuel Goodford (married to his sister Martha).

Frequently described as 'of Yeovil', Henry Pitman was a young doctor and had been studying in Italy. He returned to England around 1685 and, while visiting his family at Sandford Orcas, he heard of the Duke of Monmouth's landing at Lyme Regis and subsequent march to Taunton. Henry was persuaded to go to Taunton to view Monmouth's army and, together with his brother William and some friends they went to Taunton. This was where the trouble started...

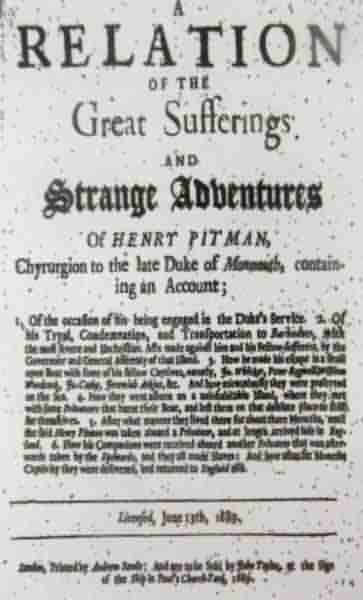

Much of the following is from the book that Henry Pitman wrote in London in 1689, entitled 'A relation of the Great Sufferings and Strange Adventures of Henry Pitman, Chyrugion to the late Duke of Monmouth'.

The Monmouth Rebellion

Following the years of the Interregnum, or the English Commonwealth, the Protestant King Charles II (1630-1685) had kept the political and religious tensions of his court and the country under control. However, his autocratic and Catholic brother James, succeeded him in February 1685.

James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, was Charles' eldest, but illegitimate, son by his mistress Lucy Walter. Monmouth had been brought up at court at his father’s side. He was a charismatic man who had shown courage and earned great honours on the battlefield. At the time of his father's death, he was living in exile in Holland. He became a natural focus for all who opposed James and was encouraged to return to England and lead a rebellion against King James.

On 11 June 1685, the Duke of Monmouth landed at Lyme Regis (from Holland), with a party of just over eighty men. The West Country was a Protestant stronghold and Monmouth's aim was to encourage West County men to join him in a Protestant rising. A large number of supporters joined him from Somerset, west Dorset and east Devon as he marched towards Taunton. His plan was to march on Bristol, and then to London in an attempt to overthrow King James and claim the throne.

Of his visit to Taunton, Henry Pitman wrote in his book "After some stay there, having fully satisfied my curiosity, by a full view both of his person and his army; I resolved to return home: and in order thereunto, I took the direct road…but…if we went forward, we should be certainly intercepted by the Lord of Oxford’s Troop, then in our way; we found ourselves, of necessity, obliged to retire back again to the Duke's forces, till we could meet with a more safe and convenient opportunity."

During the march, Monmouth raised an untrained army of West Country men numbering thousands (estimates vary from 3,200 to over 10,000). His army had three minor skirmishes with Royalist forces. Henry Pitman lost his horse and, unable to find a replacement, he "“was prevailed… to stay and take care of the sick and wounded men.” Consequently, Henry Pitman joined up with the rebels around Taunton in mid-June and served as a doctor for Monmouth’s forces. He later wrote that he didn't just treat the rebels, but "many of the King's soldiers who were prisoners in the Duke's army, using the utmost of my skill and care for both... dressing the wounded in the night time and marching by day till the fatal rout and overthrow of the whole army."

The Monmouth Rebellion, as it became known, ended on 6th July 1685 at the Battle of Sedgemoor. This, the last major battle on English soil when Englishmen took up arms against fellow Englishmen, was fought on the moors on the edge of Westonzoyland.

Henry “saw many sick and wounded men miserably lamenting the want of chirurgeons [doctors / surgeons] to dress their wounds. So that pity and compassion on my fellow creatures, more especially being my brethren in Christianity, obliged me to stay and perform the duty of my calling among them, and to assist my brother chirurgeons towards the relief of those that, otherwise, must have languished in misery; though, indeed, there were many who did, not withstanding our utmost care and diligence.”

The Aftermath and the 'Bloody Assizes'

The Monmouth Rebellion, which lasted just five weeks, was a bloodbath for the Protestant rebels, both in battle at Sedgemoor, and afterwards at the 'Bloody Assizes'. The Duke himself was taken to London and executed. James II’s pitiless treatment of Monmouth’s followers shocked the country. It is estimated that 300 rebels and 200 Royalists were killed on the battlefield and a further 1,000 rebels were killed as they fled. Many rebels were rounded up and in the following reprisals, 320 were executed and 750 were transported as bonded slaves.

Immediately after the battle, the Earl of Faversham ordered twenty two of the prisoners to be hanged on the spot; four of whom were "hanged in gemmacess" - that is, in chains. A report of the time noted "The barbarity of the soldiers, who were employed in burying the slain, was yet greater. Several unfortunate men of the duke's party, who lay wounded on the field, were thrown into the earth with the dead; and some of them endeavouring, with the little strength they had left, to crawl out of their graves, were prevented by the unfeeling soldiers, who dispatched them with their spades. The next day a new scene of slaughter was opened at Taunton, where nineteen prisoners were hanged and quartered on the Cornhill, by order of General Kirk, who caused their bowels to be burnt, and their mangled limbs to be boiled in pitch, and set up in the streets and highways. This execution was followed by several others of the like kind. The whole of those that died on this occasion, either in battle, in prison, or by the hands of the executioner, and those that otherwise suffered in their persons of fortunes, amounts to more than two thousand."

Following the Battle of Sedgemoor, Henry Pitman was arrested and “committed to Ilchester Gaol by Colonel Hellier; in whose porch, I had my pockets rifled and my coat taken off my back, by my guard: and, in that manner, was hurried away to prison; where I remained, with many more under the same circumstances, until the Assizes at Wells….”

The Assizes, which came to be known as the Bloody Assizes, were conducted in the West Country during September and October 1685. There were five judges – Sir William Montague (Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer), Sir Robert Wright, Sir Francis Wythens (Justice of the King's Bench), Sir Creswell Levinz (Justice of the Common Pleas) and Sir Henry Pollexfen. The Assizes were headed by the country’s most brutal judge, Lord Chief Justice George, Baron Jeffreys of Wem.

The Assizes began at Winchester on 26 August 1685, and proceeded to Salisbury, Dorchester, and Taunton, finally ending at Wells on 23 September. Over 1,400 prisoners were dealt with by the Assizes, and although most were sentenced to death, fewer than 300 were hanged or hanged, drawn and quartered. The Taunton Assize took place in the Great Hall of Taunton Castle (now the home of the Museum of Somerset). Of more than 500 prisoners brought before the court here on the 18/19 September, 144 were hanged and their remains displayed around the county to ensure people understood the fate of those who rebelled against the king. Public hangings and subsequent gruesome burning of entrails, quartering of corpses, boiling them in salt and dipping them in pitch for long-term exhibition was designed to strike awe into the West Country.

Henry Pitman was tried at the Wells Assizes on 23 September 1685, before Lord Chief Justice Jeffreys. In his book, Henry explained how he and others were coerced into confessing, which merely served to acquaint Jeffreys with their crimes and provide “the Bill against us, by the Grand Jury”, rather than proving them guilty of treason. As the trials began, Jeffreys made certain no one would recant his confession and prolong the trials. He “caused about twenty-eight persons at the Assizes at Dorchester, to be chosen from among the rest, against whom he knew he could procure evidence, and brought them first to their trial.” Anyone who dared to say “Not Guilty” was shown evidence to contradict such a plea. Then Jeffreys “immediately condemned [them], and a warrant signed for their execution the same afternoon.”

Henry Pitman wrote "That singular mass execution convinced most of the remaining prisoners to plead guilty and throw themselves on the mercy of the court." The rebels, including Henry, were “condemned ‘to be hanged, drawn, and quartered.’ And by his order, there were two hundred and thirty executed; besides a great number hanged immediately after the Fight. The rest of us were ordered to be transported to the Caribbee Islands.”

Henry Pitman, and his brother William, were sentenced to death. However, the Pitman brothers' death sentences were commuted to transportation because the Secretary of State, Sir Robert Spencer, Earl of Sunderland, wrote to Jeffreys early in September with his instructions “... rebels should be furnished for transportation to some of His Majesty’s southern plantations, Jamaica, Barbados, or any of the Leeward Islands.” Courtiers with business interests in the West Indies had begun bidding for the rebels as early as August. Sunderland's instructions were that -

- 200 were to be given to Sir Philip Howard, Governor of Jamaica

- 200 to Sir Richard White

- 100 to Sir William Booth, a Barbados merchant

- 100 to Sir James Kendall, later Governor of Barbados

- 100 to Sir Jerome Nepho, the Queen’s Italian Secretary

- 100 to Sir William Stapleton, Governor of the Leeward Islands

- 100 to Sir Christopher Musgrave

These grantees were to take the prisoners from custody within ten days to some of his Majesty's southern plantations, viz. Jamaica, Barbados, or any of the Leeward Islands in America, and to keep them there for ten years as indentured servants. A total of 890 prisoners were handed over. As a sidenote - a change of government in England in 1689 forced a revision of policy towards the prisoners, and in February 1690 free pardons were issued. Governor Kendall of Barbados, and others were reluctant to let their prisoners go. By 1691 half the Jamaican prisoners had been released, but not given any cash reward at the end of servitude, and so were unable to return home.

Henry and William were sold into slavery to Sir Jerome Nepho for at least ten years. He sold them on to George Penne and no doubt garnering a huge profit for himself.

Transportation to Barbados

Henry and William, together with about 100 other convicted rebels, were taken to Weymouth. From here they set sail for Barbados, a journey that took five weeks. Conditions on the ship were dreadful and Henry wrote that he "... had a very sickly passage, insomuch that nine of my companions were buried at sea.” The dead were simply, and ignominiously, thrown into the ocean.

Henry Pitman’s master in Barbados was Robert Bishop, who “grew more and more unkind unto us, and would not give us any clothes, nor me any benefit of practice... Our diet was very mean. five pounds of salt Irish beef, or salt fish, a week, for each man; and Indian or Guinea Corn ground on a stone, and made into dumplings instead of bread.” Robert Bishop eventually owed so much money that all his property, including Pitman, was confiscated and resold.

While the convicted rebels were welcome as labourers for the plantations, the government of Barbados were wary of the presence of such 'dangerous' men. Pitman, in his book, included a copy of 'An Act for the governing and retaining within this island, all such rebel convicts, as by His most sacred Majesty’s Order or Permit, have been, or shall be transported'... Henry regarded this as “inchristian and inhuman”. The Act contained rules governing the rebels during their period of servitude and regulations to prevent citizens from abetting them in any escape attempt. An example from the Act, cited by Henry, read "... one or more of the aforesaid Servants [clearly a euphemism for 'slave'] or rebels convict, shall attempt, endeavour, or contrive to make his or their escape from off this island before the said Term of Ten Years be fully complete and ended; such Servant or Servants, for his or their so attempting or endeavouring to make escape, shall, upon proof thereof made to the Governor, receive, by his warrant, Thirty-nine lashes on his bare body, on some public day, in the next market town to his Master’s town, be set in the pillory, by the space of one hour; and be burnt in the forehead with the letters 'FT' signifying Fugitive Traitor, so as the letters may plainly appear in his forehead."

The Escape

Almost as soon as he was imprisoned on the Caribbean island of Barbados, working in the harsh conditions of a cash-crop plantation, Henry began to plan his escape. He covertly began to gather a crew. He first recruited a woodworker named John Nuthall - not a prisoner, but desperate to flee Barbados because of debts. Henry also found another debtor, Thomas Waker, who was willing to join the escape. Next, Henry persuaded six fellow Monmouth rebels to join the plot. These were John Whicker (a wood joiner), Thomas Austin, John Cooke, William Woodcock (a clothier), Jeremiah Atkins and Peter Bagwell (both farmers).

Together, they gathered provisions and obtained a boat. The boat was deliberately sunk in shallow water so it would not be noticed, but could easily be made to float again when required. After gathering provisions and various supplies necessary for navigation, survival and repairing their boat, the escapees simply had to wait for an opportunity to escape.

This opportunity arrived when a local governor made a visit to Barbados. While the militias and plantation owners were distracted by the visit of the official, Henry and his fellow escapees raised the submerged boat, and paddled as fast as fast as possible until they were able to put up their sail.

With just a faulty compass, Henry Pitman navigated from island to island in the southeast Caribbean (see map). From Barbados, they sailed to Grenada, then further southeast to the small islands of Los Testigos. From here, they made their way westward to Margarita Island, off the coast of Venezuela. They tried to continue on to Tortuga, but a storm blew them back to Margarita.

Adventures with Pirates

As Henry and his crew sailed along the coast of Margarita, they saw a large group of men canoeing toward them from the island. They quickly boarded Henry's vessel. Henry recorded that there were twenty-six heavily armed Englishmen.

One of Henry's party, hoping to gain favour with the Englishmen, told them that they were escapees from Barbados and that most were former Monmouth rebels. They applauded Pitman’s crew for their resistance to the government and the Englishmen revealed that they were pirates, and had their own disagreements with the crown. Pitman and his crew were invited by the men to join them at their camp on Margarita. The pirates disclosed their intent to maraud the Spanish territories in the Caribbean, and asked Pitman and his men to join in their expedition.

While some of the escapees accepted the offer, Henry Pitman refused. The pirates did not take the refusal well and burned Pitman’s boat, hoping that the escapees would have no other choice but to join in their raid. Pitman, however, refused to join the pirates, who then took to their canoes and left the escapees marooned on Margarita.

Henry Pitman, the escapees and a captured native, built themselves simple structures for shelter and scavenged the island for food - Henry described how he found turtle especially delicious. Henry and his comrades were marooned on Margarita for about four months. Their rescue finally came at the hands of more pirates.

Two pirate ships anchored off the coast of Margarita and the pirates came ashore. The captain of the pirate ships respected the marooned men for being former rebels. It was also fortuitous that Henry Pitman was a doctor and would have been a very useful asset to the pirates. Pitman, however, reasserted that he just wanted transport, and would not become a pirate. The captain let his crew decide if they should take Pitman and his men from the island, to which they agreed- but only to taking Pitman. The other marooned men were left behind with only some fresh provisions.

Pitman’s time with the pirates was 'interesting'. The pirates captured another ship en route for Puerto Rico. They then navigated to the Bahamas, where they anchored at a pirate ‘republic’ or ‘commonwealth.’ From there, Henry Pitman boarded a ship to the British Carolinas. He then boarded a ship bound for New York. Once he arrived in New York, he bought passage back to Europe. He made landfall at Amsterdam in the Netherlands. From there, he cautiously landed off the coast of England, at the Isle of Wight, then crossed to the mainland and returned home to his family in Somerset.

Henry Pitman was naturally concerned about his legal and criminal standing. However, it soon became apparent that he had nothing to worry about. King James II, who Pitman had rebelled against, had been deposed in a bloodless 'Glorious Revolution' in 1688. Now, William III (Dutch Prince of Orange) and Mary II were king and queen of England, and Henry Pitman was no longer considered an outlaw.

... and then?

Henry's brother William died in Barbados in 1687. What happened to Henry Pitman after his return to Somerset, however, is unclear. It has been suggested that he returned to Barbados as a free man, but there is no evidence of this.

Postscript

In 1922, Rafael Sabatini published his hit novel 'Captain Blood' which was based almost entirely on the 'adventures' of Henry Pitman. In 1935 Warner Brothers released their film of the same name - a lavish extravaganza, this black-and-white 'swash-buckler' of a film, directed by Michael Curtiz and starred Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland, was nominated for five Oscars.

For Yeovil men executed for their part in the Monmouth Rebellion - click here

See Henry

Pitman's

Family Tree

Map

Henry Pitman's escape voyage from Barbados, via Grenada and the small island of Los Testigos to Margarita Island. They were initially carrying on to Tortuga, but were forced by a storm to return to Margarita Island. Total distance = over 550 km (340 miles).

Gallery

From my

collection

A postcard of Ilchester Gaol in 1836. Henry Pitman spent some time here following the Battle of Sedgemoor until he was tried at Wells on 23 September 1685.

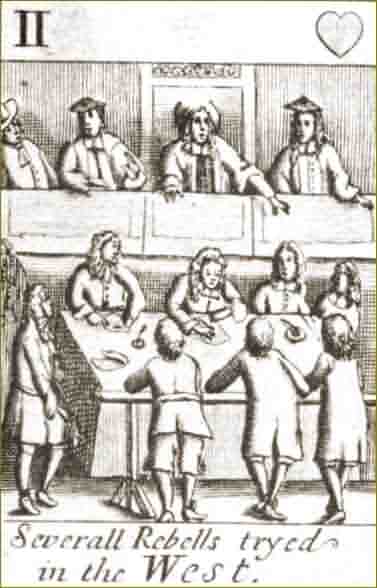

One of a set of playing cards with pictures based on the events of the Monmouth Rebellion. In this card, the two of hearts, rebels on trial are depicted.

The cover of Henry Pitman's book about his adventures, published in June 1689.

A poster for the 1935 film 'Captain Blood' starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland. The film was based on the 1922 novel of the same name by Rafael Sabatini, which, in turn, was based almost entirely on the 'adventures' of Henry Pitman.