workhouse (3)

workhouse (3)

Preston Road

A parliamentary report of 1777 recorded a parish workhouse in operation in Yeovil for up to 60 inmates. Yeovil Poor Law Union was formed on 13th May 1836 and its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 47 in number.

"The Yeovil Union comprises several other parishes, amongst which are East Coker, West Coker, Ilchester, Martock, Montacute, Podimore, and South Petherton. The House is situated about half a mile from the Kingston Gate, on the road to Preston. The total population of the various parishes, according to the census, was 28,463. The total expenditure of the Union for the year 1851 was £10,773 15s 5d, of this amount, the parish of Yeovil expended about £2,348 7s 3d." (Vickery)

Yeovil Union Workhouse, or to give it its proper title the Yeovil Union Public Assistance Institution, was built in 1837 at the north side of Preston Road in Yeovil. The architect was Sampson Kempthorne and adopted his model hexagonal plan which he also employed for the workhouse at the nearby Taunton Union. A two-storey entrance block at the south contained a porter's room on the ground floor, with the Guardians' board room above. To the rear, three wings for the various classes of inmate (male/female, infirm/able-bodied) radiated from a central hub. The hub had kitchens on the ground floor and the master's quarters above. Windows in the hub provided views in each direction over the segregated inmates' yards. The workhouse could accommodate 300 paupers and a hospital for 60 patients was subsequently added.

The workhouse was not just for the poor of Yeovil, as the Workhouse Union comprised 36 parishes in the area with a total population (in 1871) of 28,853.

Uniforms for both sexes were usually made from fairly coarse materials with the emphasis being on hard-wearing qualities rather than on comfort and fit. Men were issued with jackets of strong woollen fustian cloth, waistcoats, breeches or trousers, striped cotton shirts, a neckerchief, cloth cap, rubbed worsted stockings and shoes. Women and girls were issued with strong chocolate-brown 'grogram' gowns, calico shifts, petticoats, stays, day caps or strong straw bonnets, blue handkerchiefs, black worsted stockings and woven slippers.

The 1841 census listed 65-year old Francis Masters as the Master of the Workhouse, his wife Susanna was Matron and their 40-year old son Francis Jnr was their Assistant. Also resident were a Schoolmaster, a 15-year old schoolmistress, a Porter and a Nurse. There were 179 'inmates' including 85 children aged between 14 and 2 months, of whom 47 were listed as orphans, 7 were listed as deserted and 21 were listed as bastards.

The routine was strict and penalties were harsh - the Sherborne Mercury reported in its edition of 10 December 1842 "John Partridge, Isaac Trott, John Harrison, George Bartlett, John Bartlett and Benjamin Wilton were sentenced, the first two to 21 days hard labour each, and the remaining four to 14 days each, for refusing to obey the orders of the Master of the Union House, and for disorderly conduct."

Hunt's Directory of 1850 had the following entry - "Union Workhouse, Preston Road; Chaplain, Rev John Langdon; Surgeon, Wm Tomkins; Master, John Howarth; Mistress, Jane Howarth."

In 1851 Phillip and Mary Foale were Master and Matron and again there were a resident Schoolmaster, Schoolmistress, Porter and Cook. There were 177 'inmates' but only 6 Glovers and one Leather Parer but there were 27 House Servants and 16 Farm Labourers.

Slater's Directory of 1852-3 gave a little more information on the staff of the Workhouse -

| Governor | Philip Foale | |

| Matron | Mary Adams Foale | |

| Schoolmaster | William Squires | |

| Schoolmistress | Elizabeth Perry Loader | |

| Clerk to Board of Guardians | Elias Whitby | |

| Chaplain | Rev John Langdon | |

| Surgeon | William Fancourt Tomkins | |

| Relieving Officers | Thomas Horwood and Thomas Johnson |

In 1861 George and Ann Murrant were Master and Matron and there was a schoolmistress, porter and cook living in. The 1861 census was somewhat kinder in that 'inmates' were only listed by their initials instead of full names. However 11 were listed as idiots, one as insane, one as weak-minded, two were listed as dumb from birth and two as blind from birth - giving some indication of the social 'care' role of the institution. In Victorian times, indeed well into the twentieth century, there was a standard categorisation of people with moderate to severe intellectual disabilities (although all these terms are now considered pejorative or derogatory). These terms are frequently found in the census returns. An "idiot", with an IQ of 0 to 20, was an intellectually disabled person, or someone who acted in a self-defeating or significantly counterproductive way. An "imbecile", from the Latin word imbecillus, meaning weak, or weak-minded included people with an IQ of 21 to 50. A "moron" (a twentieth century term) was a person with an IQ of between 51 to 70. A "cretin" was a person suffering a condition of severely stunted physical and mental growth due to untreated congenital deficiency of thyroid hormones. The term "lunatic" derives from the Latin lunaticus which originally referred mainly to epilepsy and "madness" as diseases caused by the moon and was a somewhat informal term referring to people who were considered mentally ill, dangerous or unpredictable.

|

"A woman

named

Hannah

Russell,

104

years

old,

entered

the

Yeovil

Workhouse

last

week as

a

pauper." |

In 1871 James and Mary Stone were the Master and Matron, assisted by a Schoolmistress, Porter, Nurse and a Cook. There were 165 residents all listed as "Paupers", including 3 idiots, 10 imbeciles and 2 lunatics. 27 were glovers, perhaps indicating the start of a recession in the industry,

In 1881 John and Jessie Rodger were Master and Matron, together with a Schoolmaster, Porter and Nurse. The 135 residents were referred to as "Pauper Inmates" of which over 40 were aged 70 or more with four people in their nineties and ten were in their eighties. In addition 6 were classed as imbeciles, 4 were of 'weak intellect', 2 were lunatics, 1 epileptic and 1 blind. Consequently some 40% of the 1881 workhouse population were effectively 'in care'.

Frederick and Caroline Wilton were Master and Matron in 1891. No schoolmasters or mistresses were in residence although 22-year old Susannah Brooks was employed as the workhouse's Industrial Trainer. There was also a Matron's Assistant, a Sick Nurse and a Porter. 114 'Pauper Inmates' were recorded, again with 30 aged 70 or more, of whom 9 were in their eighties and 2 in their nineties. Eight people were listed as imbeciles and two as lunatics so the 'in care' section of the workhouse population had dropped to around 30%.

Frederick and Caroline Wilton remained Master and Matron in 1901 and the staff now included an Assistant Matron, two Infirmary Nurses, and Industrial Trainer of Children and a combined Assistant master & Porter. 26 were aged over 70 with 8 in their eighties and 2 in their nineties. 31 were children under 14 with two women noted as being "in confinement". The "Infirmities" column became less concerned with mental problems, although there were still two imbeciles, one person suffering from hysteria and one 'supposed lunatic under observation', and more general conditions were being entered including two people with 'epilepsy from childhood', two with phthisis (tuberculosis), two with ulcerated legs, two with palsy, and one each deaf & dumb, paralysis, chronic rheumatism, heart disease, general debility, blind, ruptured and syphilis,

The workhouse later became Summerlands Hospital and only the entrance, or administration, block of the original workhouse now remains.

Conditions in the Workhouse

1928 -

Experiences

of an

investigative

monk

The following is from an article published in the Western Chronicle recalling conditions in Yeovil's workhouse in the year 1928. It is reproduced here in full. When, in 1959, former casual wards of the then Summerlands Hospital were about to be demolished, the hospital secretary stated they had by that time been out of use for 25 years. He described them as a memorial to the bad old days, saying that the nine buildings to be pulled down were "originally used as casual wards for tramps and vagrants and as isolation blocks. 30 or 40 wayfarers used to be accommodated for the night". The original cells, "just like a prison", were still to be seen, with heavy doors with triple locks and bolts, and with peep-holes for the Warden to look through. A steam disinfector for clothes, dated 1901, was crumbling into rust, and the secretary called it the hospital's 'Rocket'. In 1928, the Rev Brother Douglas, a Franciscan monk, wrote a series of articles for the Western Gazette, under the title 'On the Road'. In these he described the conditions of workhouses he had visited in the guise of a tramp. Most showed a general lack of facilities, and the fare was exceedingly poor, though Brother Douglas was able to say of Shepton Mallet Casual Ward that "it was the best conducted" in which he had been, and when he and his fellow tramps left, they were given a voucher for a mid-day meal, to be presented to a tradesman in Castle Cary, "this being the only one received, with the exception of that at Frome". But his experience at Yeovil was of a different nature, the following being a copy of his report. "We arrived at Yeovil late in the afternoon, and I have a very unhappy tale to relate of our experiences in this casual ward. The Porter had evidently not drunk of 'the Milk of Human Kindness'... He conducted us to the reception room, which was evidently a disused stable, and there, by the light of a hurricane lamp placed in the window, took all, except our private papers (which he could not touch) away, and laid them on the window ledge. We were then taken to the casual ward (where there were two or three other casuals), and handed over to the "Tramp Major". By the dim light of the hurricane lamp, I saw there was about a foot of water in the bottom of a bath. We were not asked about a bath, but were at once taken along a stone passage, with cells on one side - six, if I recollect rightly - the "Tramp Major" opening the door of No 4, where I found four blankets, hurried away with the lamp, leaving me in complete darkness to find what sort of place I was in. I felt around a bit, and before he returned with the usual supper, had found that there was a hammock lying on the stone floor, upon which I began to spread my blankets in the darkness. When he returned, I asked about a bath, and made my way to the bathroom mentioned, where a man of about 60 or so was standing upright, in a naked state, in the foot of water, and trying to cleanse himself by douching the water over him. I approached the official mentioned, and said it was impossible for me to bath like that, and he simply replied "You can wash in that water, or not at all." I at once decided 'not at all'. There was no heat in the cell, and the shirt and blankets I used were just as the other occupant had left them - probably, judging from the dirtiness of the shirt, as numerous other occupants had left them! At any rate, I had to fold them and leave them in the morning for my successor! The bread given us, both at night and in the morning, was very dry, and we both had difficulty in cutting it with a knife. We had to eat all our meals sitting on a blanket from our 'bed' on the stone floor of the cell. The cells were bitterly cold, and the hot-water pipes near were not even slightly warm. In the morning, when we proceeded to the bathroom to wash, there was no soap at all and only one small towel for the five of us to use! There were no buttons on the shirt I had to wear at night. I have no hesitation in saying that all the cells were in the same condition as that in which I spent the night, for my companion and the others were loud in their complaints of a sleepless night owing to the cold. We were put to work on a cross-cut saw during the day, but it was so cold that we did not make any progress, and at 12 o'clock came back into the wretchedly cold cell for dinner. The piece of cheese was so evil looking that I could not attempt to eat it, so my companion and I sealed it in an envelope and took it to the Editor and another gentleman who saw - but did not eat - any portion of it. On the second night we slept in a room with seven bed-frames, which were mostly occupied. It was very cold, and in the morning we thankfully departed after wiping ourselves in a dirty towel - more than grateful to have learned how casuals live, or rather exist." Brother Douglas also mentioned that there were texts nailed to the door of each cell, his being 'God is Love'. He was, he says, thunderstruck that such a thing could have been exhibited in such a place by anyone. He was told that one of the Guardians provided them and commented "What a pity that Guardian does not spend a night in the casual cell himself, in order to see exactly how these men are treated." During the 1939-45 war, the buildings were used by the A.R.P. (a warden's post designated as Post B was located here) and nursing staff to receive bomb casualties. The new Summerlands Hospital which arose on the site, started with the commencement of the first three wards in 1967, completed two years later. A further ward was added, and the hospital formally opened in 1973 by the then mayor, Alderman Mrs Hazel Brown. Further improvements and additions have taken place since then, and all that remains of the former Union Workhouse of 1837, which had once accommodated 300 paupers, is the building fronting Preston Road.

|

![]()

The following description is from the Somerset Historic Environment Record -

Workhouse administration block, dated 1837. Local Stonework cut and squared with plain Ham stone quoins and window dressings Welsh slated hipped roof with 2-brick chimney stacks set asymmetrically. 2-storey, 11-bay facade of 3:1:3:1:3 pattern, with single offsets to bays 4 and 8 and double offset to bays 5-7. Simple pediment to central projection, bearing dates 1837 and 1968. Sliding sash windows: ground floor windows have 2 upper and 1 lower pane; first floor 3 upper and 2 lower panes. Central ground floor window has slightly proud surround with crude pediment over. 2-matching single storey wings each side: Rear elevation much altered.

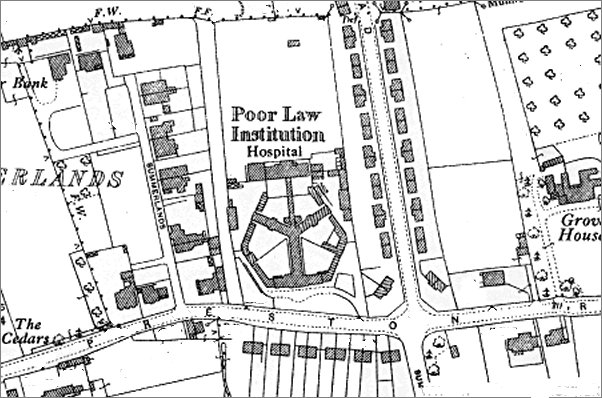

map

Map based on the 1929 Ordnance Survey showing the hexagonal layout, typical of Sampson Kempthorne, of the original workhouse buildings.

gallery

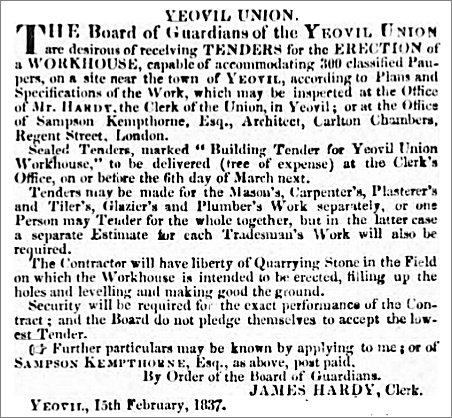

This notice requesting tenders for the erection of the new Workhouse that would be erected in Preston Road was placed in newspapers across the country during February 1837.

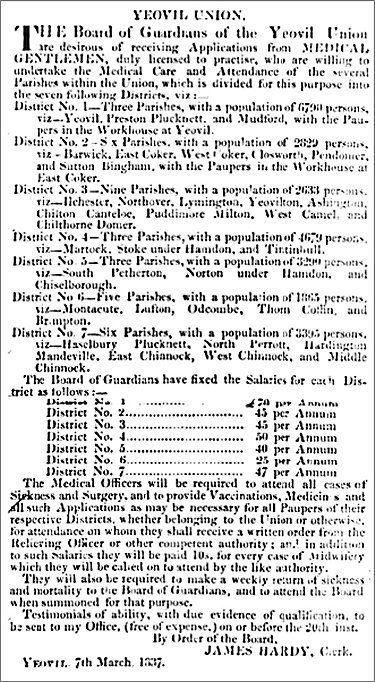

This notice, again placed nationally in newspapers, seeking doctors for the Union is interesting as it lists the various districts covered by the Union and their respective populations in 1837. Note also that the Yeovil doctor's salary would be £70 per annum (just under £100,000 at today's value).

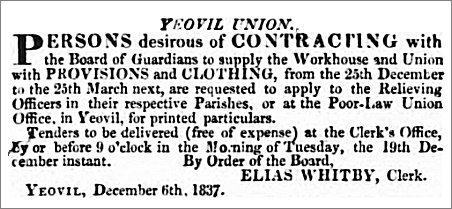

By the end of the year the Yeovil Union was ready to start contracting for supplies to the new Workhouse as seen from this nationally-placed notice.

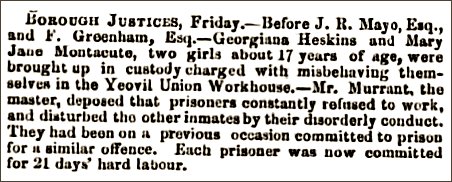

Misbehave and just see what happens! - from the Somerset County Gazette of 9 March 1867.

This photograph

features in my

books 'Yeovil

From Old

Photographs'

and 'Secret

Yeovil'

The Yeovil Union Workhouse, Preston Road, photographed around 1890.

Women in workhouse issue uniforms (not Yeovil) photographed around 1905.

Men in workhouse issue uniforms (not Yeovil) photographed around 1905.

From the Cave

Collection

(colourised),

Courtesy of South Somerset Heritage Collection

An

early 1960s

photograph of

the old

workhouse

building, seen from the junction of Preston Road and

Summerleaze

Park.

From the Cave

Collection,

Courtesy of South Somerset Heritage Collection

An early 1960s photograph of the old workhouse building, seen from Preston Road.

...and seen from behind the massive retaining wall facing Preston Road. Photographed in 2013.

This photograph

features in my

book "Yeovil

In 50 Buildings"

The main Preston Road elevation seen from the east. Photographed 2017.

The main Preston Road elevation seen from the west. Photographed 2013.

The date 1837 in the pediment is the date of foundation of the original buildings and 1968 refers to the major redevelopment of the site into Summerlands Hospital.