Yeovil Art & Technical Institute

Yeovil Art & Technical Institute

Kingston

This is an article written by David Gibbs and I am grateful for his permission to reproduce it here.

There was a secondary school in Lower Kingston as long ago as 1850, roughly where the hospital is now. Originally, it was a private school, and then it became Yeovil County School and eventually Yeovil School. In 1938 Yeovil School moved to new buildings in Mudford Road and the old premises became Yeovil Art and Technical Institute. The Technical School for boys aged 13 to 15 years of age came into being in 1946. I started there in the September of the following year.

Each morning a little gang of us, gathered from the surrounding villages by the Southern National and Hutchings and Cornelius buses and disgorged in The Borough, made our satchel-swinging way through St John's churchyard into Vicarage Street, past the Central Cinema and the little sweet shop next door, turned the corner by the Chelsea Tea Rooms into Princes Street; then along Princes Street, past the Sunshine Fruit Stores opposite the Jolly Farmer Cafe, and on until we came to Vincent's motor-car showroom; then we crossed the road to the pavement that skirted Bide's Gardens, on past the bus shelter and the Red Lion pub and so to the Tech which was just a few yards further on. But there's no sign of the place now; the buildings were demolished in January 1968.

It wasn't a very big school. The intake for each year of the two-year course was about 90 pupils. Two thirds of the intake was destined to study Engineering, the remainder building.

The catchment area was vast. There were boys from Yeovil, llminster, Chard, Crewkerne, South Petherton, Langport, Curry Rivel, Sherborne, Castle Cary and Wincanton. Some came from strange places I had previously never heard of like Bradford Abbas, Henstridge and Templecombe.

If you lived more than three miles from the school, Somerset County Council paid your fare providing there was a service bus or train to travel on. If not, you got a bicycle, or a bicycle allowance, like the lads from Barwick and Stoford and from East Coker. As a result of all the travelling, boys arrived at school at all sorts of strange times. For instance, it was usually about half past nine before the Langport contingent used to roll in and although school didn't end until four-thirty in the afternoon they used to be off again at half past three. Even the Henstridge lot went well before four. I often wished I came from Langport, or even Henstridge, rather than Merriott.

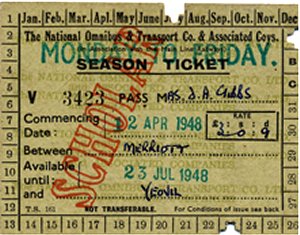

A Southern National bus season ticket, costing £3 0s 9d per term.

l didn't think much of the Tech at first. It was all very strange after a village school. For a start there were different teachers for different subjects, and also different classrooms for different subjects, so we seemed to be constantly changing from subject to subject, teacher to teacher, and room to room.

Many of the subjects were strange too, like workshop technology, Engineering drawing, and geometry. I loathed geometry. A simple thing like a circle that in the village school was nothing more than a 'ring' suddenly became very complex, having a radius, a circumference, a diameter, and degrees and things. Triangles, on the other hand, had corners they called angles, and it might be isosceles or equilateral instead of being just a three-sided square.

Of course, it being a technical school, much emphasis was put on practical work and for budding Engineers like me that meant metalwork. The metalwork classes were held in a workshop located on the ground floor of an industrial building in Market Street, next to Vincent’s bodybuilding workshop.

The upper floor of the building was used for storing hides, so it was a bit smelly. But here there were lathes, milling machines, grinders, shapers, sheet metal working machines, brazing and soldering equipment, benches, vices and all manner of hand tools. They had been enthusiastically gathered together by a teacher called Mr Gwilliam, a man who played a leading role in establishing the teaching of Engineering in Yeovil, first in the Technical School and later in the Technical College. However, most of the machinery he had managed to lay his hands on had seen better days and had probably been discarded by local industry.

But discarded machinery or not, Gwillie's workshop provided many a future craftsman with his first taste of the real Engineering world. We drilled and filed, hammered and forged, turned and milled - activities well outside the scope of village schools. And we actually made useful things, like a matching toasting fork and poker with twisted shanks and ringed ends, made to last a lifetime. Indeed, my poker lasted for years and was indestructible; I might still have it somewhere. If only there had been someone with initiative to harness all this newly acquired expertise Britain could have lead the world in pokers and toasting forks.

I quite enjoyed metalwork but there were other classes I enjoyed more, particularly English. Perhaps Mr D L Smith had much to do with this. Dudley was fun. What's more he was a very good teacher. He used to delight us with a piece of poetry about eating an orange and it had a punch line about 'spitting the pips in your face'. We plagued him to recite this poem just for the spitting bit, and he often obliged, invariably, and I think somewhat deliberately, spraying the front two rows of the class in the process. One of the best, was Dudley.

Then there was the geography teacher, Mr James, who sported a RAF-type moustache that earned him the nickname of Flying Officer Kite, later abbreviated to just 'Kite'. He seemed to take great delight in punishing minor misdemeanours by roller-stencilling a blank map of the world in your exercise book and then keeping you in at break time to shade in the British Empire in pink. There was a lot of pink empire about back in those days.

The head of the school was Mr Pryor, 'JJ' to staff and pupils alike but only when he was out of earshot. JJ was a small man, but what he may have lacked physically he made up for by a very positive personality. He was very strong on discipline. He resorted to caning if the misdemeanour deserved it, so you didn't tangle with him. If JJ told you to button your jacket, you buttoned it, and quick. And if you saw JJ walking towards you along Princes Street you wasted no time in putting your cap on. After all, he had made it quite clear that our caps, with their segments of two shades of blue and the YTS badge on the front, were to be worn and not stuffed in pockets. What’s more, underneath each cap he expected there to be a well-behaved boy. Alas, boys being much the same then as they are now, both objectives were never totally realised.

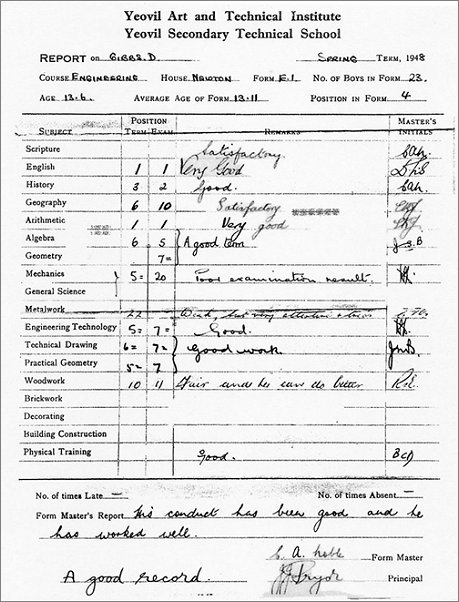

A school

report

Some boys went far beyond defying JJ by not wearing their caps. They actually climbed to the top of a high playground wall so that they could look through a window to see the nude model posing for the students in the Art School next door. Then they would report back to those of us too timid to risk such an adventure what they had seen - exaggerated no doubt, and exaggerated even more by the time the information they provided had been processed by our awakening adolescent imagination. Phew!

It was probably the very same wall climbers who had the courage to slip out of school at lunchtime - it was strictly forbidden to leave the premises - to buy the sepia-tinted Health and Efficiency magazine from Douglas Cant, the newsagent just across the road, next to the Rendezvous café. The playground barter rate, even for a much-thumbed Health and Efficiency, was at least five Hotspur comics in good condition, because even Rockfist Rogan of The RAF couldn't compete with the pictures of the coyly posed female nudes even if they did have an important part missing.

The playground was the only recreational area in the school. There was no playing field. Instead, every Wednesday afternoon the whole school had to go crocodile fashion all the way to Mudford Road recreation ground.

We played

cricket in the

summer and

association

football in the

winter. Cricket

failed to

interest me to

any great extent

but I thoroughly

enjoyed the

football and my

greatest joy was

finding, much to

my surprise,

that I could

play football

well enough to

play for the

school First XI.

And a very good

team it was too.

No other school

was a match for

us, except

perhaps

Stoke-under-Ham

Stanchester

School. Our

toughest game by

far was when we

played them in

the final of the

Pittard Shield

on the famous

Huish slope. We

won 2-1. And the

following year,

just a few short

weeks after Alec

Stock's

giant-killers

had beaten Bury

and Sunderland

in the FA cup,

we played on the

now-famous slope

again, this time

against Grass

Royal School,

and we won

handsomely by

eight goals to

one. What a

thrill it was to

play at Huish!

We played

cricket in the

summer and

association

football in the

winter. Cricket

failed to

interest me to

any great extent

but I thoroughly

enjoyed the

football and my

greatest joy was

finding, much to

my surprise,

that I could

play football

well enough to

play for the

school First XI.

And a very good

team it was too.

No other school

was a match for

us, except

perhaps

Stoke-under-Ham

Stanchester

School. Our

toughest game by

far was when we

played them in

the final of the

Pittard Shield

on the famous

Huish slope. We

won 2-1. And the

following year,

just a few short

weeks after Alec

Stock's

giant-killers

had beaten Bury

and Sunderland

in the FA cup,

we played on the

now-famous slope

again, this time

against Grass

Royal School,

and we won

handsomely by

eight goals to

one. What a

thrill it was to

play at Huish!

The victorious school 1st XI, 1948. David Gibbs is fourth from left, back row.

Now Huish, like the Technical School, has gone. Huish lives on in the new stadium at Houndstone, or so they say. As for the Tech, well, I suppose that lives on too, in the form of the college in llchester Road. Certainly many of us who were the first pupils at the Technical School were also the first part-time students at llchester Road, attending classes in the big house long before the present buildings were constructed. And I wouldn't be a bit surprised if somewhere in the present-day workshops there lurks at least one item of machinery from Gwillie’s Market Street workshop. Could be present day students still make pokers and toasting forks, but if they do I bet they're not as good as the ones we used to make.

|

Yeovilians remember.... Thanks to Bud Martin for the following - "I was part of the last group of boys attending the school in the final three years before it closed (1963?) and clearly remember my first day there. Apparently, JJ had remarked upon the 'frail, weedy looking bunch' that made up my years' intake and forbade the older lads from being too rough in the initiation 'ceremony' which took place on the alleyway steps leading to the playground. We too, enjoyed the metal & woodworking facilities which resulted in me making my first electric guitar. Indeed, that instrument (crudely made!) set the course of my life as a lead guitarist for the Dale Fender & The Beatmakers band (later becoming the Penny Arcade) and touring Germany in the mid '60’s. I'm still professionally playing Rock 'n' Roll although the original guitar is long gone. Happy days!"

|

gallery

Courtesy of

David Gibbs

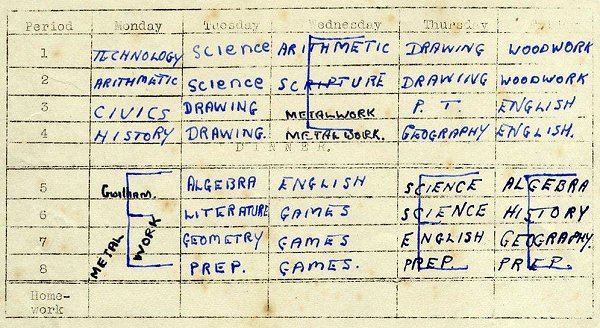

David's school timetable.

Courtesy of

David Gibbs

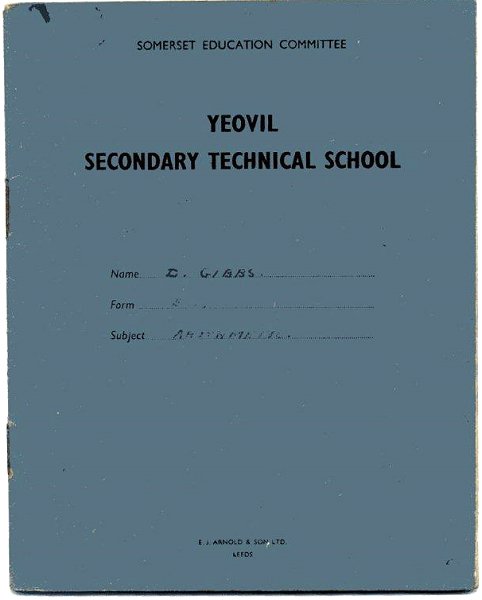

.... and the cover of an exercise book.

Courtesy of

David Gibbs

This is the school team on the occasion of playing Stoke Secondary Modern School in the final of the Pittard Shield, April 1948. The Tech won, 2-1.

Back row, L to

R: Stroud (West

Coker), Purchase

(East Coker),

Young (Stoke U

Ham), Hardy

(Yeovil),

Glanville

(Langport), King

(Yeovil), Hunt

(Donyatt),

Pearce (West

Coker?)

Front row, L to

R: Hussey

(Yeovil), Gibbs

(Merriott),

Sandford

(Yeovil), Raisin

(East Chinnock),

Coates (Charlton

Mackrell).

David has added

boys' names and

where they came

from, the latter

to indicate the

wide catchment

area of the

school. It was

more a South

Somerset

Technical School

than simply a

Yeovil Technical

School.

David says "The school provided the shirts, I believe they were green with white collars. The boys had to provide their own shorts and socks. It seems we all managed to acquire white shorts for the special occasion but were rather less successful with regard to socks! The match was played on the famous Huish slope, the slope being clearly discernible in the photograph. In the background, Bruttons Brewery."